Not Cool Ep 24: Ellen Quigley and Natalie Jones on defunding the fossil fuel industry

Defunding the fossil fuel industry is one of the biggest factors in addressing climate change and lowering carbon emissions. But with international financing and powerful lobbyists on their side, fossil fuel companies often seem out of public reach. On Not Cool episode 24, Ariel is joined by Ellen Quigley and Natalie Jones, who explain why that’s not the case, and what you can do — without too much effort — to stand up to them. Ellen and Natalie, both researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (CSER), explain what government regulation should look like, how minimal interactions with our banks could lead to fewer fossil fuel investments, and why divestment isn’t enough on its own. They also discuss climate justice, Universal Ownership theory, and the international climate regime.

Topics discussed include:

- Divestment

- Universal Ownership theory

- Demand side and supply side regulation

- Impact investing

- Nationally determined contributions

- Low greenhouse gas emission development strategies

- Just transition

- Economic diversification

References discussed include:

- Paris Agreement

- Positive Investment

- SumOfUs

- Oil Change International

- Untapped ambition: addressing fossil fuel production through NDCs and LEDS (Cleo Verkuijl, Natalie Jones, Michael Lazarus)

- Universal Ownership in the Anthropocene (Ellen Quigley)

You can use the financial system, and use investors and banks, to delegitimize the fossil fuel industry. Strip them of financing, and also strip them of the moral license to operate. And once you don’t have a moral license to operate, that’s when governments can get in and start doing interesting things.

~ Natalie Jones

Ariel Conn: Hi everyone and welcome to episode 24 of Not Cool, a climate podcast. I’m your host Ariel Conn. This week we’ll be focusing more on actions you can take to address climate change. We all know we should be driving less, flying less, and eating less meat. But things like where you bank and whether you express your climate preferences to your 401k manager could have a direct and powerful impact on fossil fuel companies. And then, since individual action, no matter how powerful, isn’t sufficient, we’ll also look at some of the various types of global policies that could be most effective at slowing down both carbon emissions and fossil fuel production. And we’ll talk about much more. For this discussion, we’ll be joined by Ellen Quigley and Natalie Jones who are both researchers at the Center for the Study of Existential Risks, also known as CSER, at the University of Cambridge.

Ellen is a Research Associate in Climate Risk & Sustainable Finance. She works with CSER on addressing climate change in the investment policies and practices of institutional investors. She holds a B.A. in English literature from Harvard College, an MSc in Nature, Society, and Environmental Policy from the University of Oxford, and a PhD from the University of Cambridge.

She is also the Advisor to the Chief Financial Officer of Responsible Investment at the University of Cambridge; and a Postdoc Researcher at the Centre for Endowment Asset Management at the Cambridge Judge Business School.

Natalie works on global justice and existential risk at CSER, and recently submitted her PhD thesis in international law at the University of Cambridge. She consults for the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) as a Staff Writer for the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, which is the de facto record of multilateral environmental negotiations.

Before coming to Cambridge, Natalie worked as a Judges’ Clerk at the High Court of New Zealand, and has completed shorter stints at the Stockholm Environment Institute, the Urgenda Foundation Climate Litigation Network, and the Inter-American Association for Environmental Defence. She holds undergraduate degrees in law and in physics from the University of Canterbury, and an LLM from the University of Cambridge.

Ellen and Natalie, thank you so much for joining us.

Natalie Jones: Thanks for having us, it’s great to be here.

Ariel Conn: You’re both doing sort of different work — one of you is working on financial issues; one of you is looking at climate change through the lens of policy. And before we get into some of the more specifics about what you’ve both been working on, I was hoping you could both just briefly talk about how you started looking at climate change through these different perspectives.

Natalie Jones: Okay, I can go first if you like — this is Natalie speaking. I did my undergraduate studies in law; I was legally trained. And I was always quite taken with the idea of how law and policy can be a tool for the purposes of change. And I got out of law school, I was working as a judge’s clerk, and I was like, this isn’t really it. And actually that year I got this incredible opportunity to attend the UN Climate Conference — it was COP19. It was this time when the world was preparing for what was going to become the Paris Agreement, and I was there as a youth activist.

Around same time I started as a volunteer with a local youth climate activism organization in New Zealand — it’s called Generation Zero. So, at this time I was really experiencing attempts to change or influence policy regarding climate change at the local government level — with stuff like public transportation and bus lanes and cycle lanes; these really small scale things — all the way up to what was happening at the intergovernmental level.

And I eventually went back as a New Zealand youth delegate in the following year and also in Paris, COP21 — with, again, like a New Zealand youth group. And also working with a coalition of other young people who were trying to influence what happened in that agreement. It really catapulted me into the policy realm and I decided to keep on working in this area.

Ariel Conn: Excellent. Ellen?

Ellen Quigley: I think I started to freak out about the climate crisis in my very early 20s, as I was finishing undergrad. I actually took four years off in between degrees and was a community organizer back in my hometown of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, and worked part-time in an alternative bookstore and just did a lot of stuff on the ground. But, some of it worked and a lot of it didn’t, which was actually really helpful. And I worked on so many losing election campaigns, I can’t even tell you. A bunch of us put together an arts and environmental festival that brought in about 15,000 people, which was kind of the main large-scale effort — garlic self sufficiency projects and stuff like that — to kind of bring some humor and art into the space.

But I think what I realized is that I didn’t know what the levers were even, let alone how to pull them, when you consider that any local activism was going to be counteracted by just tremendous forces that really couldn’t be fought at that level. So I went back to school to do a master’s in geography and environmental policy, and then got really obsessed with economic geography, and then joined a divestment campaign, and then learned a little bit too much about that whole question, which complicated my views such that divestment became one of a list of tactics needed to shift the financial sector.

Ariel Conn: I’m assuming that is connected to a paper that you recently published on Universal Ownership theory. Before we go any further with that, I was hoping you could just explain what universal ownership theory is, and maybe also what universal owners are.

Ellen Quigley: I personally think that Universal Ownership theory is the paradigm shift that’s required to make a whole suite of changes that would fit well into that framework — to transform our financial system; to address not just catastrophic climate change, but issues like inequality, and forced migration and mass animal extinction. These are all things that count as externalities, if you’re an economist. I think that they should be internalized in the current system. The only way you do that is with the Universal Ownership lens. Universal Ownership: the traditional definition is a very large fund — like a pension fund, or a university endowment, or a sovereign wealth fund — that basically owns a more or less representative slice of the financial system or the economy as a whole. That can mean that they just own shares in every sector and in every geography, which would describe almost every fund that we can think of.

I also think it encompasses basically all young people who have any money at all invested in any which way; anyone who’s invested in a tracker fund, which is just a fund that tracks all of the stocks in a particular index, so you basically own a little slice, a representative slice, of the whole market — anybody who owns one of those for at least a medium amount of time. And young people in general, plus all these huge funds like pension funds, would count as universal owners. Because what unites them all is that what affects them much more than the performance of any given stock is the performance of the economy as a whole. They could outperform the market, and that would be nice and everything, but that pales in comparison to the effect that the performance of the whole economy has. Alpha is outperforming the market in financial speak, and Beta is the market itself: the base performance of the market as a whole.

And I think that what we need to do is to have those groups realize that any externalities that one company produces, the cost of those get picked up elsewhere in the portfolio. So there’s no escaping them; there are no real externalities if you’re a universal owner. If you believe that and if that is indeed the case — which it sure seems to be — there needs to be coordination among universal owners to push for things that can only happen at a systemic level. For example, different countries feel pressure to keep regulations at a minimum to attract multinational corporations. A universal owner could help push those companies to meet standards that would cross borders. You could have a 1.5 degree compliant portfolio requirement for every company that you own, and if you had a large enough ownership share within all of these companies, they could no longer argue that they are at a disadvantage relative to their competitors, or their peers, because they would all be basically forced to meet the same standard.

And by the way, the thing that is currently happening on that front is that a bunch of shareholders are working together to pass shareholder resolutions and other things like that — just resolutions that shareholders can vote on at annual general meetings of these companies. But what we see is, A, most of these resolutions are about disclosure only. And disclosure is just a means to an end; it’s not an end itself. And the other thing is that almost all of these shareholder resolutions are advisory, which means that even if you win them, the company doesn’t necessarily have to adopt them. So I personally think that shareholders should be using the tool they definitely have, which is the power to vote in and out the board. This seems like a much more direct route to influence whether or not these companies are en route to rapid decarbonization, which is what we desperately need.

And I think it’s better for everyone if people don’t feel as though they have to take a hit that their competitors don’t have to take. This also applies to inequality, which is an intensifier of a lot of the effects that we see from catastrophic climate change. If you care about the performance of the economy as a whole, you want a robust middle class — whereas if you have vast inequality or a large poverty stricken population, that isn’t good for the whole system. So universal owners should care about that as well.

Ariel Conn: So just to make sure I’m clear, universal owners already exist. I guess what you’re suggesting is they’re not influencing either their power or corporate decisions as much as they could?

Ellen Quigley: Yeah, they already exist, but they may not realize that they are universal owners. They might just think, “Oh, I’m a pension fund.”

Ariel Conn: Okay.

Ellen Quigley: Some of them already are spreading the word about this; they have very much this paradigm in place, but it’s by far not the majority of people I think we could consider to be universal owners. So they need to kind of familiarize themselves with the concept, but also what sorts of actions would naturally flow from the concept.

Ariel Conn: So for example, if I have funds in Fidelity or in Vanguard or in some other organization like that, and they send out notifications that there’s some vote coming up, you’re saying that we should be paying close attention to those votes, so that we can be influencing who is on the board. Is that correct?

Ellen Quigley: Yes. I mean, currently Fidelity is not quite as bad, but Vanguard has among the worst voting records, and they’re the second largest fund manager in the world. So there’s a huge lever to be pulled.

Ariel Conn: So when you say that, do you mean people who are invested in Fidelity are more likely to vote, or the impact of votes are more meaningful at Fidelity? Or something completely different?

Ellen Quigley: This is a really good way to clarify what I’ve been trying to say. Fidelity and Vanguard will vote on your behalf. And most people don’t even realize that they are voting; it’s all just happening within a kind of central decision making apparatus. And I think almost none of them would ever consult with their actual beneficiaries about how they would want to vote, which is also an issue, you might argue.

Ariel Conn: And so how do people who are invested change that?

Ellen Quigley: Well, you should write to Vanguard, and also a lot of these companies themselves have shareholders. If you are part of an institution, you can engage with these fund managers as companies; I know that sounds strange. But as an individual, that’s a relatively rare position, relative to what your roles might be with pension funds and so on. If you’re a beneficiary of a pension fund, you should definitely ask your pension fund to engage with your fund manager and try to get them to change their practices on this. Frankly, they don’t hear from too many people, so even being bothered by one large institution is often enough to at least nudge things somewhat. But if you’re an individual, and you invest via Vanguard, I would highly recommend writing to them — and write to the whole board, write to the chief executive, et cetera. Again, not too many people actually contact them for any reason, so it’s actually pretty high impact. Some of these things turn on five emails from members. It’s crazy.

Ariel Conn: Are there templates or something like that? Is there guidance somewhere, or are we sort of doing this blind?

Ellen Quigley: There isn’t enough. And honestly, we should probably get going on that and do something. But, I do know two organizations that are doing interesting things on this front. One of them is something Natalie and I have both been involved with, Positive Investment Cambridge, or the kind of umbrella group Positive Investment. And they’ve put out a tool that allows you to switch commercial banks and explain why — and write to the old bank and give the reasons why. This relates to fossil fuel funding, specifically. And that, actually, I think is even more high impact than writing to a fund manager, because these banks actually are providing direct financing of new projects, so it’s really, really high impact. And also they really desperately don’t want to lose your deposit.

The other group that I know does work around this is SumOfUs. And they occasionally do letter writing campaigns on particular issues, and they have a tool that you can use to select which pension fund you’re part of, or what fund manager you have, and then you can write to them directly to get them to put pressure in various places in the system that there isn’t enough.

Ariel Conn: That’s actually really interesting. You’re suggesting that we can just look into how our banks are investing and loaning out money, and if we don’t approve, we can switch to another bank that is more environmentally friendly?

Ellen Quigley: Yeah, that’s actually probably one of the most high impact things you can do as an individual. People are more likely to switch spouses than bank accounts. And banks know this, so they’re terrified to start losing customers or gaining the knowledge that they’re likely to be scaring off new customers. Especially young people, because they know if they sign up young people, they’ll basically have them forever. If you do switch banks, and you have a lifetime of deposits on the books for the bank, they are able to lend out on the basis of those deposits. If enough people did this, and especially if large institutions did this, they would actually be able to functionally lend less, if they have fewer deposits on their books. But that said, I actually think the effect would come long before there is a measurable effect on their actual ability to lend. Because the fear of large institutions switching away is a really big stick for a bank.

Natalie Jones: You might be wondering, well, if I move my money away from Barclays, or from another bank that does actually fund a lot of new coal or oil and gas products, who do I switch to? There are some organizations that have done some quite good work on which banks are worse than others, or which banks are better. And one of those is Positive Investment, but in the US also I I’m thinking of Oil Change International, who have quite a good report comparing all of the commercial banks and kind of ranking them.

Ellen Quigley: Although Personally, I would say go for a credit union or a cooperative bank or a building society. This might not actually be true in the US, but almost everywhere else that I know of, credit unions have nothing to do with capital markets. They tend to loan locally; a lot of them will have a mandate to improve lives within their own geographical sphere. Through some of these tools, you can actually figure out which ones are not so much avoiding causing active harm but actively doing something good.

Ariel Conn: If you were, say, a large institution like a university or some other big organization, would you say then that it’s more impactful to divest from fossil fuel companies or to change banks? Or should not be an either/or?

Ellen Quigley: I mean, I think we should be doing all of the things we can. Depending on your theory of change, both tactics could be good. I think that there is a direct effect on banks that is hard to argue with. I would also say you could bring in some of the reasoning in the divestment movement and kind of intensify the effect of switching banks if you announce that it has that effect on public discourse that you want, which is the effect that divestment has. Divestment doesn’t have a direct effect on where capital goes — it doesn’t shift capital. But it does have an effect on how we view companies. And I think that if you switch banks and explain publicly why, and put pressure on them to change their lending practices, I think that could have a huge effect, especially if you are a well-reputed institution.

Ariel Conn: Wow, okay. I’m going to come back to your Universal Ownership theory paper, and I still am sort of trying to make sure that I’m getting terminology and understanding what these different concepts are. So how does being a good universal owner differ from various types of responsible investing? And I’d actually intended to ask you about this Positive Investment program. Is that only banking?

Ellen Quigley: No, that’s just one project. But yeah, basically I have the perhaps unpopular view that most ESG investing — that’s Environmental, Social and Governance investing; SRI investing, which is Socially Responsible Investing; or RI, which is Responsible Investing; or Ethical Investing, is all kind of the worst of both worlds. Because almost all of that does not involve the announcement that we were talking about earlier. It doesn’t have the effect on social discourse that you might have by saying publicly, “We don’t want to be associated with this company that’s causing harm.” But it also doesn’t shift capital, because almost all of it happens within what I call the secondary market. The secondary market is all of public equity, so that’s every company that’s listed on a stock market. When you first list on a stock market, you do what’s called an Initial Public Offering, or an IPO. When you do that, what you’re doing is you’re basically selling shares for the first time so that you are spreading the ownership around.

And when that happens, the company that’s listing on the stock market gets an influx of capital. So, it can do things like buy out all of its founders, or expand greatly, or have a growth plan that can be fully funded with the money that comes in from the people who’ve just bought these shares. After that point, they don’t get any money from when their shares are bought and sold. They can raise more money, by issuing bonds, for example, which means that they do get an influx of debt financing to do something. When they go to a bank for a bank loan, they can also do project financing that way — that’s more new money coming in. Or they can issue more shares. But just buying and selling shares on the stock market does nothing to the company. It doesn’t help the ones that you would want to help and it doesn’t hurt the ones that you might want to hurt. It doesn’t matter to Exxon who particularly owns their shares unless they announce the fact that they’re selling them, in which case there is this public effect.

The social discourse shift is meant to result in government action: that’s what needs to happen. There isn’t good enough evidence to suggest that it affects share price at all — let alone enough to make a difference — or cost of capital, which is the other thing people cite. So the effect really is supposed to be that you put pressure on a sector to be regulated by the government in various countries, which is exactly what happened with apartheid in South Africa; enough pressure was put on through the divestment movement that countries started to enact sanctions against South Africa, and that’s what brought about the end of the regime. Boycotts and sanctions were what did it, but those were government legislative actions, not actually shifting capital. There was really none of that. It was a social movement.

Natalie Jones: And I think this works in really well with what we’re going to talk about a bit later on with the policies on the supply side.

Ariel Conn: I think would be good to bring some of the questions about policy in now as well. So, if you could explain the difference between demand side and supply side policies when it comes to fossil fuel use and extraction.

Natalie Jones: Yeah. So, a demand side policy on fossil fuel use is, I guess, a policy that would tend to constrain or limit the demand for fossil fuels, and thereby limit the amount that are burned and the amount of carbon emissions. So, it’s the idea that you reduce the emissions by constraining the demand for the coal, the oil and the gas. It’s basically everything that nearly everyone has been talking about for a couple of decades now. So, an emissions trading scheme where you trade emissions allowances, and ideally have a cap on those; or a carbon tax, where you impose a tax on emitting; or measures to improve energy efficiency, or promote renewable energy. These are all examples of what many people would call a demand side policy. Now this, as I say, has been really the predominant way of thinking about that kind of climate policy, at least among academics and economists.

But what this has tended to ignore is, in a way, the other side of the equation — and that is what happens at the supply end. The rationale for tackling the other side comes partly from the idea that it might be more economically efficient if you tackle it from both sides — e.g, there are fewer companies who make, who extract, who produce the fossil fuels than their are companies who burn them. You reduce the transaction and the administrative costs if you regulate at both ends; obviously, we need the demand side policies, but we also need ones at the supply. And so in terms of what those look like, it could be things like a moratorium or a ban on new coal mines, on new oil exploration, on oil extraction, on gas exploration, on gas extraction; also on the transportation, so on new infrastructure like pipelines.

On a micro scale, it can look like the denial of permission for individual projects where the planning permission is being requested. And the government or court says, “No, actually, that’s not in line with my climate goals, or public health, or any one of a myriad of reasons.” Another example is ending the subsidies on fossil fuel production side. And so these are all kinds of measures that a government can implement, and increasingly we have been actually witnessing this happening. And the example of moratoria on oil exploration or production: we’ve had this in the cases of New Zealand, Costa Rica, France, a handful of others. And we’ve seen moves to stop coal production in Germany and Spain. Those are a few examples where these kind of moves are already happening, and these countries are really at the forefront.

But, just to kind of link this back to what Ellen was talking about, these are some of the policies that can happen when you have the public support. What Ellen was talking about is how you can use the financial system, and use investors and banks, to delegitimize the fossil fuel industry. Strip them of financing and also strip them of the moral license to operate. And once you don’t have a moral license to operate, that’s when governments can get in and start doing interesting things — not only on the demand side, but also on the supply side. And there’s some interesting research, actually, that indicates that these kind of policies actually enjoy more public support than the demand side ones — because in a way, they’re more upfront. It’s like, “Okay, we’re going to ban oil extraction, we’re going to ban coal,” which is, in a sense, more of a root cause of the problem, rather than a complicated economic instrument that many people have issues getting their heads around, like a carbon trade scheme. And it often has more of a direct impact on people’s lives, in terms of the immediate environmental effects of these products, and the immediate health impact. So that’s quite an interesting finding.

Ellen Quigley: There’s also the demand side of the equation when it comes to the financial side of things. And there, you actually see more emphasis on the fossil fuel companies and not on the demand side of the equation. And I think that that’s a bit unfortunate, because let’s say you did or didn’t divest from fossil fuels themselves. You would still have exposure to all of the sectors that use the most fossil fuels. So, the auto sector, utilities, steel, cement: those you actually could — again, if you had a Universal Ownership lens — you could work together to rapidly decarbonize. Because again, all of those sectors have this issue that they fear that they will fall behind their competitors if they’re forced to do something that the others aren’t. And if you could decarbonize these high fossil fuel demand sectors rapidly, then it would make the argument about shutting down coal mines moot, because they wouldn’t be attractive anywhere in the world, even in places in which there wasn’t a moratorium.

Ariel Conn: Okay, so I’ve got three questions to try to make sure I’m better understanding all of this. I mean, ideally, we want to stop extraction and production, but right now we can’t because these companies are too big and powerful. Is that premise correct as a starting point?

Natalie Jones: Yeah. So it has been the case that the pressure exerted by these companies has been a major barrier. And a lot of people include it as a reason, for instance, why the Paris Agreement itself hasn’t got any mention of fossil fuels, or these kind of supply side issues; also, as to why at the national level, there’s been less action on this than many would have liked. So that’s an issue. Another one is that, I suppose, the level of awareness around these being actual policies that you can do, and the research around that. I think only in the last handful of years has this been a topic of major academic study, and you’re starting to actually see studies like, “Okay, so if Norway stopped oil extraction, what would happen? What would the economic effects be? Would there be like a spillover effect, whereby other countries would just make more?” And the answer is actually, no, you wouldn’t have as much spillover as you might expect. So, having more of an understanding about the downstream impact of these kinds of changes is, in my opinion, helping a lot.

Ariel Conn: So, we have this premise that it has been difficult, obviously, to stop production and extraction. And if I’m understanding what you guys are saying, we can divest, which doesn’t actually take money out of the system, but it helps delegitimize the companies. Is that correct?

Natalie Jones: Yes. It’s also worth mentioning that, that isn’t the only action that can help with the delegitimization. Lots of examples in recent years, when non-governmental groups have applied various forms of pressure, e.g, a protest in a coal mine — there was a massive one in Germany recently, where you had a few thousand people rocking up in a coal mine to stop it from operating on one particular day. Obviously it doesn’t have much of an impact on the long-term operation of that coal plant; it has a massive impact in terms of raising the public awareness of this being not a good state of affairs, not a good activity.

Ellen Quigley: It might also be worth just reiterating something that Natalie brought up earlier, which is about subsidies and lobbying activity. You’re asking, “Is it because these companies are simply too powerful?” Well, they are incredibly powerful, and part of that is because they help to shape regulation that benefits them — including subsidies that mean that the cost of using these products never matches the actual price. Let alone the cost of all the externalities, like air pollution that affects people’s health, and so on so forth, and definitely not including the cost of catastrophic climate change. So those are two things that absolutely need to shift.

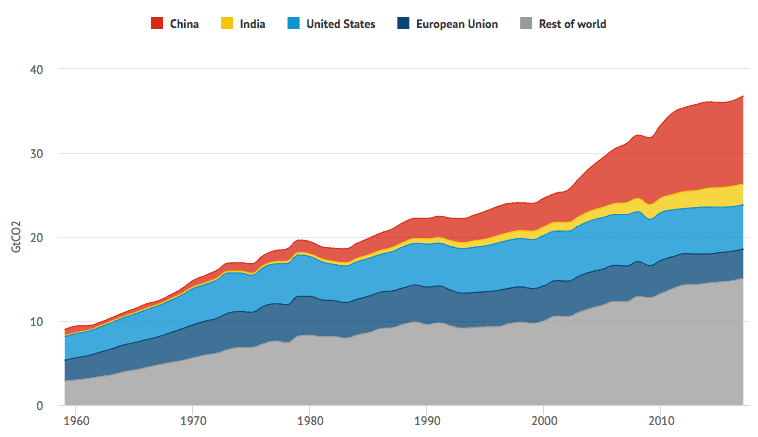

Natalie Jones: Yeah. And also on that point, there are some absolutely incredibly horrible statistics out there, along the lines of more money is spent by governments on these subsidies every year than is spent on renewable energy investment, for instance, or spent on basically any other policies that would help the climate. You see the same trend with some international financial institutions, where they are investing often more in fossil fuels than in renewable energy. That really, really needs to change.

Ariel Conn: So we have the premise that for many reasons, the oil companies and the fossil fuel companies are very hard to stop. Divestment and other means can help delegitimize that. And then with banking, either by people or institutions changing their banks, or I’m guessing there’s other ways to convince banks not to loan to these companies — that can help start to defund them. Is that correct?

Ellen Quigley: Yes. And actually, it’s also worth mentioning that if divestment did extend past public equity and into other asset classes, such as bonds, for example, it actually could starve fossil fuel companies of the financing that they require to do things like exploration and development, or build a new pipeline or whatever else. A lot of that is debt financed. And some of these companies come to the market twice a year to issue new bonds to get more money to work with. So, if everybody who had divested from fossil fuels also ensured that they weren’t buying any of the bonds of these companies, and that they didn’t have a relationship with a bank that was using their deposit to finance fossil fuels, that could make a really big difference, actually.

The way you establish whether a fossil fuel company is serious about transition doesn’t have anything to do with their current assets, but where all of their new money is going. So, what you care about is, A, if they’re doing something terrible — which, I mean, none of them is aligned properly with the 1.5 degrees scenario. So I think we can say, where’s their new money coming from? Their new money is coming from bank financing and from bonds, sometimes issuing new shares, but we really don’t see much of that these days. And then where is their new money going? So what is their capital expenditure? What is their research and development spending? What are their acquisitions? That’s where they’re headed. If you look at those numbers, that gives you an idea of whether or not they are on a path to transition. So, if you see that a company has 97% of their capital expenditure going towards more exploration and development for extraction of fossil fuels, you know you’ve got a problem and that you shouldn’t be buying the bonds of that company.

Natalie Jones: And this is what we see in the case of companies like BP and Shell, for instance, and I highly suspect in the case of Exxon and Chevron as well.

Ariel Conn: I’m going to keep going with my clarification here in a minute. But, I want to bring this back to the idea of the universal owners. When you’re talking about things like purchasing the bonds, how do you keep track of what’s happening?

Ellen Quigley: Well, most universal owners are going to be operating through fund managers, and it’s literally their job to do that. Let’s say that a universal owner has a fund manager and they’ve been told not to purchase new bonds that are issued in fossil fuels. That means that if a whole bunch of investors had had that policy when Saudi Aramco listed earlier this year, you might have seen less of a success in the part of that newly funded institution. That bond was oversubscribed, but a lot of people didn’t realize that they were buying it, and wouldn’t have consented to that. But it was such a large issuance that it automatically was included in bond indices, which meant that a whole bunch of people automatically bought it.

And that just seems like something that shouldn’t happen in this day and age. And the only way that you start to question that, and to question automatic inclusion of bond issuances like this, is by having that conversation with fund managers. That is something that anybody who has a divestment mandate should just go back to their fund managers and insist applies to their bond portfolio. They’re doing exactly the same thing; it’s often the same companies.

Ariel Conn: So if, say, you’re with an institution that has divested from fossil fuels, is it still possible that the portfolio includes bonds for those very companies?

Ellen Quigley: Yeah, often. It’s just a different asset class, and people just don’t think about the other asset classes when they’re doing this work. And that’s fair enough, because a lot of the people who are putting pressure on institutions to divest don’t necessarily have a degree in finance, nor should that be required. So it’s just a level of detail that would bring all these other asset classes into view, but they’re absolutely essential when it comes to new money being allocated to new fossil fuel projects, which is really what we need to stop.

Ariel Conn: This brings me to another question that I had specifically about the Universal Owners theory paper. And that was that it seems that basically divestment isn’t enough; that even if you are part of a group that is divesting from fossil fuels, there’s still a lot of ways that you are putting your money towards either the burning of fossil fuels, or, as it sounds like, bonds that are associated with them. Can you talk a bit more about where the investments are going and what people should be looking out for? And then also, how do you remain invested and not have money in something that’s associated with burning fossil fuels?

Ellen Quigley: That’s an excellent question. Personally — I mean, I don’t have very much to invest — but mainly I just invest directly in solar construction bonds and stuff. In the UK, there are actually quite a few options for things like that; in Canada as well, it turns out. There are quite a few options for those who’d rather just directly invest in something good and help make it happen. This is usually called impact investing, but I think it applies to kind of a broader swath of investments now that there are commercially viable solar installations and wind farms and so on and so forth. For a pension, it gets more complicated, but that’s where I think — you know, universal owners don’t get to just exempt themselves from the fate of the whole of the economy. They have to figure out what to do with Shell. So, either they have to help Shell transition, if that’s possible — and they have to do it rapidly; let’s be clear — or they need to wind it down. But they have to take responsibility either way.

And if you’re a universal owner you care what happens to workers in the economy as well, because you need a healthy, vibrant workforce and a robust middle class to have a working economy. You can’t exempt yourself from the fate of the coal miner or the coal mine. It’s all your responsibility if you’re a universal owner, so you need to either shut things down or transition them. You have to be part of all of that, no matter what the asset class; it’s part of your mandate and purpose, I would argue.

Ariel Conn: And so in this instance, are you differentiating between a universal owner in sort of an ideal sense, and a pension fund holder at a university?

Ellen Quigley: I think that I’m speaking from an idealized standpoint, unfortunately, but it’s still true. The largest pension fund in the world, which is GPF in Japan: the Chief Investment Officer of GPF will tell you that he’s a universal owner, because he can’t stock pick his way out of the climate crisis, for example. It’s both idealized in that we would hope that people like him would think that way, because it’s absolutely essential to fixing our current problems, but it’s equally true that that is the situation. It’s just whether or not people recognize it as such.

Ariel Conn: What advice do you have for people who do want to be responsibly investing, but who also don’t have a background in finance and who are reliant on some major funder pension?

Ellen Quigley: First of all, switch to a credit union with a good green track record, and then find impact investments in your jurisdiction. And when I say impact, I don’t mean anything on the stock market. I don’t think you can have a true impact investment through buying a stock in a company that’s listed on the stock market, because it’s the secondary market, for reasons that we’ve discussed. I’m a particular fan of diversifying the types of institutions that we have in our economy. So I particularly target coops: I like to fund cooperatives in renewable energy and energy efficiency, and so on and so forth — that’s my preferred method, but reasonable people disagree about this. I just think those are the first two things that you can do that have a real direct impact.

But then the other thing you need to do is go to all the institutions of which you are a part and push for a whole broad swath of actions that would actually allow us to collectively transition rapidly and justly. And that would look like a whole bunch of the things we’ve already been discussing. It means firing the directors of companies that do not have a 1.5 degree-compliant plan. But also it has to be reflected in their capital expenditure and in their research and development, spending, et cetera, as we’ve discussed.

Ariel Conn: Let’s switch over to some of the policy stuff. On the finance side, we’ve got these steps of delegitimizing and defunding the fossil fuel industry. Once we’ve done that, then we turn to countries to sort of take the final step. And I was hoping you could talk a little bit more about what ideally that would look like, and what we’re seeing today.

Natalie Jones: I guess what ideally that would look like is a bit like what I’ve already been speaking about — so these policies which you would have on the supply side as well as on the demand side. In the case of any major economy, or in fact any economy that is currently extracting fossil fuels, you basically want that to stop. And not necessarily immediately: we know that to stay within like a global warming limit of 1.5, we need to half emissions by 2030 and reach net zero by the middle of the century. So we need to stop quite quickly, which basically means not investing in any new fossil fuel projects. It means closing some substantial amount of the ones that we already have. And these kind of questions, in addition to the finance realm, also need the government policy to provide the incentives and the constraints which will allow that to happen.

But also all these policies have to be undertaken with a sense of justice for the workers and communities who will be impacted, who often are relatively poor and marginalized, possibly — and also, historically speaking anyway, haven’t really been involved in the decision making processes. So it’s vitally important to involve those who you’re going to affect when you close down these industries, as must happen. Because what cannot happen is leaving people behind in a systematic way, as we have seen in some cases, e.g, in the UK with the closure of coal mines. And what we are actually seeing, quite hearteningly, in the cases of the countries who are actually adopting these policies — I’m going to speak about New Zealand, because I am in New Zealander — slightly biased — but adopted a policy regarding the banning of all new offshore oil and gas exploration. Which, of course, was not a perfect policy by any means; it still allows for the extension of existing exploration leases, for instance. But what has been a crucial part of that is a planning process regarding what happens with the workers and the particularly affected regions.

So that’s one crucial element of it. Another crucial element is equity, so looking at which countries maybe have extracted more than others in the past and have gained all the profits associated with that; and then looking at ideally, which countries would stop quicker than others. That’s a really active research area that needs more work, I think, but there are some good papers there. So I looked at this in the context of the international climate regime, so under the Paris Agreement where all countries have to make their pledges, right? So the whole idea is that they have these NDCs, which stands for nationally determined contributions, whereby if you’re a country, you hand in basically your plan regarding what is going to happen over the next five years. And most of them were handed in just around the time of the Paris Agreement and are due to be updated or enhanced in about a year’s time. And so what we found when we looked at these is basically that hardly any of them even mentioned production of fossil fuels in their countries.

And that’s not surprising, because there is no indication in the Paris Agreement that countries ought to include this; as I mentioned, it’s all about what’s happening on the demand side and on emissions reduction. So these NDCs include lots of targets along the lines of, we’re going to reduce our emissions by a certain percentage regarding like a given base year, a given target year — all of that kind of stuff, which is good and great, and we need more of that, and we need those pledges much higher ideally, because there’s a massive emissions gap, which is the gap between what countries have planned to emit and then what we can emit in what’s called the carbon budget for staying under a 1.5 or two degree limit. So that’s one aspect of the NDCs, but the aspect that we looked at was if they mentioned production. And what we found was that only one country, which was India, mentioned that it has a tax on coal production, which is a really great supply side policy from India. And it’s great that it’s mentioned it in this international context, because one of the interesting elements of these NDCs is that, I mean, everyone else reads them; they get scrutinized by the international community.

And so, even if the Paris Agreement isn’t mentioning oil, coal and gas, if you’re a country that has a policy like this, you can include it in your NDCs; there’s nothing stopping you from doing so. And so what would be quite interesting is if all the countries that had already started making these policies would include them in their reporting, which is these NDCs, and also this other document, which is our low greenhouse gas emission development strategies, which are like NDCs but more long-term and they aren’t mandatory; they’re voluntary only. The key point is that countries have these two mechanisms where they can say, “Here’s our plans, here’s what we’re doing.” In both cases, they actually have an option, and they can say, “Actually, we’re taking these other kinds of policies — we’re banning coal mines, we’re banning oil exploration.” And that can help institute a norm that can help with this process at the international level, which we’ve been talking about kind of at the national level: of making it more of an accepted idea that you would close down the supply.

So what we’ve been talking about is at the national level removing the moral license; this is part of removing the moral license at the international level — is by including these in these key documents; in these key documents which form part of the Paris Agreement. So what we’re seeing in those documents is a very small minority of cases that actually mention these measures, but when countries actually mention the production of fossil fuels, they mostly do so either in the context of reducing the emissions associated with the operation of the fossil fuel industry itself so, reducing emissions from the flaring and venting of methane gas, or making the extraction operations slightly more energy efficient, which would reduce the emissions that go into drilling, and all those kinds of things.

And the other aspect in which production is mentioned is in the context of economic diversification and just transition. And we’ve already kind of touched on a just transition, this idea where you need workers to be carried along rather than left behind. And economic diversification is kind of associated: it’s where a country relies, really, on oil and gas exports, for instance, and really needs to move its economy away and have other sources of national income, which is a really large problem. But what these countries have included in the NDCs is an acknowledgement of this and maybe some plans for moving away. But that’s rather different from actually including plans to reduce the problematic area. It doesn’t necessarily go along with that. So that’s, I guess, the two interesting findings from a study that I did with some other people recently.

Ariel Conn: So in that study, you talk about six elements that you would like to see included in the NDC’s and LEDS. And you’ve just been talking about a couple that a handful of countries are actually implementing. But there are, I think, four that basically aren’t included at all. Could you maybe talk a little bit about some of the elements that countries haven’t included yet that you think are really important?

Natalie Jones: Yeah. One of these elements is, I guess, the pathways and measures to reduce the production of fossil fuel. So this is what I was talking about, where only in one case, in the case of India, we really see the inclusion of a policy that would constrain production of fossil fuels — where in actuality a number of countries are taking these measures, but they’re not reporting them. And this kind of comes back to this point of, you can take a measure, and that’s great — like you can make a policy in your national context and it will have an effect, but you can magnify that if you report it. The other aspect that’s been basically missing is what we’ve touched on regarding equity. So with the case of NDCs, when countries are making pledges regarding emissions reductions, they are obliged to also include information regarding the equity of that, and why they think that that is an ambitious and just response, taking account of their national circumstances. But what would be great is also if countries would include the same equity analysis of why their policies and measures on the supply side are also just.

Another thing is the general context, and I guess before you actually go into any of these, what are the measures you ought to be taking. But the other thing is just acknowledging that you have a problem — or not even that you have a problem, but that you are a producer of fossil fuels. In these documents, you see countries reporting all kinds of things like, “We are extremely vulnerable to the effects of climate change.” You see countries reporting, “Here are our main industries.” You see a lot of background information. And what would be really helpful is if countries also included it in that background information, “Yeah, and we extract coal and here’s our projections as to how that’s going to change in the future,” or, “Here’s our plans to increase the production of coal,” — which many countries in fact have, particularly regarding oil and gas, plans to increase. So it’s owning up to that, because that’s the starting point for where these plans work from.

There are a handful of countries that have started implementing these policies, but are not including them in these documents which report back to the international process. Of course, there are many other countries that have so far not implemented these policies, and there are others that maybe have, but could improve. There’s a lot more space for action. Individuals can be really instrumental in where they put their votes, in terms of individuals or parties which have these policies. Because I know in the key western states there are candidates or parties that do have better manifestos on this, and others which do not. So that’s one thing that individuals can do.

Ariel Conn: I think this is a nice transition to ask my final question. And that is, are you still hopeful that we’ll be able to take enough action in the next 10 to 30 years to keep global temperatures ideally below 1.5 degrees Celsius, but even below two?

Ellen Quigley: Well, you have to be hopeful. It is technologically feasible. I believe that it is possible. I think the only thing that’s lacking is political will, but that’s starting to be generated on a scale and at a speed that I don’t think any of us imagined about a year ago. And because of the school strikes for the climate, because of Extinction Rebellion, finally civil society is starting to put pressure on politicians to do what’s necessary, which is — let’s be clear — a complete transformation of our economy. But the funny thing is, we’ve done that before. We did that during World War Two — almost every industrialized nation rejigged all of its industrial processes in a shorter period of time than we have now to cut emissions in half. So I think it’s really just, can we rouse ourselves to rise to the challenge? I think we can; I just hope we will.

Natalie Jones: And on point of this being an unprecedented or nearly unprecedented change, an alternative way to look at that is that we are standing on the brink of potentially one of the most exciting decades in human history, with the most innovation and the most change. So we have this opportunity to do something really massive and to be part of something great. Which I think is not a matter of hope, but it’s more a matter of we have to do this, and so this will change everything, and don’t think too much about it.

Ellen Quigley: Yeah, full steam ahead. But also the change will come — the status quo is not an option. So, we either have a really terrible forced transition that leaves a bunch of people behind and means that we end up in a catastrophic death loop, climate wise. Or we do it in a way that, as Natalie is saying, takes advantage of human curiosity and ability to cooperate, and get something tremendous done in a short period of time. We’re absolutely capable of that.

Natalie Jones: Yeah. The real challenge, I think, which is something I’m quite concerned about, is doing it in a just way, so not leaving behind those who are most impacted either on the industry end or on the impacts end. Basically not doing it in a way that militarizes borders and leaves people out in the cold, as it were. You said something, Ellen, like, “We’re rising to the occasion.” I just want to caution against this kind of universalist “we” a little bit. This is a whole other podcast.

Ariel Conn: I really like this idea that we’re sort of on this precipice. And if we do this right, we’re sort of initiating this huge change for the better, I guess. This should be a really exciting time, actually. I think that’s a really nice perspective.

Natalie Jones: It’s important that whether you have been working on it for decades and decades or if you’re just coming to it, just hop on board, is what I have to say.

Ellen Quigley: I mean, we could end up with a world in which it’s a lot more fair and equal, and we all breathe much cleaner air, and get a lot more exercise and eat healthier food. And that is an option in all of this; it’s just one that has to be created politically — and technologically, but primarily politically.

Ariel Conn: All right. Well, thank you both so much for joining. This has been really interesting for me. I learned a lot.

On the next episode of Not Cool, a climate podcast, we’ll be joined by the executive director of Protect Our Winters, Mario Molina, who will talk about what it takes to get both the technological and financial pieces in place to address climate change, as well as the political and cultural will necessary for change.

Mario Molina: The information is there. The science is far, far ahead of the public’s knowledge. The policy solutions are far ahead of the public knowledge, and the technological and financial solutions are actually far ahead of what’s being implemented. But what’s keeping us from deploying them at scale, and in rapid fashion, is the lack of political will.

Ariel Conn: As always, not only do I hope you enjoyed this episode, but if you did, I hope you’ll consider liking it, sharing it, and possibly even leaving a good review.