FLI Podcast: Is Nuclear Weapons Testing Back on the Horizon? With Jeffrey Lewis and Alex Bell

Nuclear weapons testing is mostly a thing of the past: The last nuclear weapon test explosion on US soil was conducted over 25 years ago. But how much longer can nuclear weapons testing remain a taboo that almost no country will violate?

In an official statement from the end of May, the Director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) expressed the belief that both Russia and China were preparing for explosive tests of low-yield nuclear weapons, if not already testing. Such accusations could potentially be used by the U.S. to justify a breach of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT).

The CTBT prohibits all signatories from testing nuclear weapons of any size (North Korea, India, and Pakistan are not signatories). But the CTBT never actually entered into force, in large part because the U.S. has still not ratified it, though Russia did.

The existence of the treaty, even without ratification, has been sufficient to establish the norms and taboos necessary to ensure an international moratorium on nuclear weapons tests for a couple decades. But will that last? Or will the U.S., Russia, or China start testing nuclear weapons again?

This month, Ariel was joined by Jeffrey Lewis, Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies and founder of armscontrolwonk.com, and Alex Bell, Senior Policy Director at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Lewis and Bell discuss the DIA’s allegations, the history of the CTBT, why it’s in the U.S. interest to ratify the treaty, and more.

Topics discussed in this episode:

- The validity of the U.S. allegations –Is Russia really testing weapons?

- The International Monitoring System — How effective is it if the treaty isn’t in effect?

- The modernization of U.S/Russian/Chinese nuclear arsenals and what that means

- Why there’s a push for nuclear testing

- Why opposing nuclear testing can help ensure the US maintains nuclear superiority

References discussed in this episode:

You can listen to the podcast above, or read the full transcript below. All of our podcasts are also now on Spotify and iHeartRadio! Or find us on SoundCloud, iTunes, Google Play and Stitcher.

Ariel Conn: Welcome to another episode of the FLI Podcast. I’m your host Ariel Conn, and the big question I want to delve into this month is: will the U.S. or Russia or China start testing nuclear weapons again? Now, at the end of May, the Director of the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, the DIA, gave a statement about Russian and Chinese nuclear modernization trends. I want to start by reading a couple short sections of his speech.

About Russia, he said, “The United States believes that Russia probably is not adhering to its nuclear testing moratorium in a manner consistent with the zero-yield standard. Our understanding of nuclear weapon development leads us to believe Russia’s testing activities would help it to improve its nuclear weapons capabilities.”

And then later in the statement that he gave, he said, “U.S. government information indicates that China is possibly preparing to operate its test site year-round, a development that speaks directly to China’s growing goals for its nuclear forces. Further, China continues to use explosive containment chambers at its nuclear test site and Chinese leaders previously joined Russia in watering down language in a P5 statement that would have affirmed a uniform understanding of zero-yield testing. The combination of these facts and China’s lack of transparency on their nuclear testing activities raises questions as to whether China could achieve such progress without activities inconsistent with the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty.”

Now, we’ve already seen this year that the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, the INF, has started to falter. The U.S. seems to be trying to pull itself out of the treaty and now we have reason possibly to be a little worried about the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty. So to discuss what the future may hold for this test ban treaty, I am delighted to be joined today by Jeffrey Lewis and Alex Bell.

Jeffrey is the Director of the East Asia Nonproliferation Program at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute. Before coming to CNS, he was the Director of the Nuclear Strategy and Nonproliferation Initiative at the New America Foundation and prior to that, he worked with the ADAM Project at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the Association of Professional Schools of International Affairs, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and he was once a Desk Officer in the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy. But he’s probably a little bit more famous as being the founder of armscontrolwonk.com, which is the leading blog and podcast on disarmament, arms control, and nonproliferation.

Alex Bell is the Senior Policy Director at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Previously, she served as a Senior Advisor in the Office of the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security. Before joining the Department of State in 2010, she worked on nuclear policy issues at the Ploughshares Fund and the Center for American Progress. Alex is on the board of the British American Security Information Council and she was also a Peace Corps volunteer. And she is fairly certain that she is Tuxedo, North Carolina’s only nuclear policy expert.

So, Alex and Jeffrey, thank you so much for joining me today.

Jeffrey Lewis: It’s great to be here.

Ariel Conn: Let’s dive right into questions. I was hoping one of you or maybe both of you could just sort of give a really quick overview or a super brief history of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty –– especially who has signed and ratified, and who hasn’t signed and/or ratified with regard to the U.S., Russia, and China.

Jeffrey Lewis: So, there were a number of treaties during the Cold War that restricted nuclear explosions, so you had to do them underground. But in the 1990s, the Clinton administration helped negotiate a global ban on all nuclear explosions. So that’s what the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty is. The comprehensive part is, you can’t do any explosions of any yield.

And a curious feature of this agreement is that for the treaty to come into force, certain countries must sign and ratify the treaty. One of those countries was Russia, which has both signed and ratified it. Another country was the United States. We have signed it, but the Senate did not ratify it in 1999, and I think we’re still waiting. China has signed it and basically indicated that they’ll ratify it only when the United States does. India has not signed and not ratified, and North Korea and Iran –– not signed and not ratified.

So it’s been 23 years. There’s a Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty Organization, which is responsible for getting things ready to go when the treaty is ready; I’m actually here in Vienna at a conference that they’re putting on. But 23 years later, the treaty is still not in force even though we haven’t had any nuclear explosions in the United States or Russia since the end of the Cold War.

Ariel Conn: Yeah. So my understanding is that even though we haven’t actually ratified this and it’s not enforced, most countries, with maybe one or two exceptions, do actually abide by it. Is that true?

Alex Bell: Absolutely. There are 184 member states to the treaty, 168 total ratifications, and the only country to conduct explosive tests in the 21st century is North Korea. So while it is not yet in force, the moratorium against explosive testing is incredibly strong.

Ariel Conn: And do you remain hopeful that that’s going to stay the case, or do comments from people like Lieutenant General Ashley have you concerned?

Alex Bell: It’s a little concerning that the nature of these accusations that came from Lieutenant General Ashley didn’t seem to follow the pattern of how the U.S. government historically has talked about compliance issues that it has seen with various treaties and obligations. We have yet to hear a formal statement from the Department of State who actually has the responsibility to manage compliance issues, nor have we heard from the main part of the Intelligence Community, the Office of the Director for National Intelligence. It’s a bit strange and it has had people thinking, what was the purpose of this accusation if not to sort of move us away from the test ban?

Jeffrey Lewis: I would add that during the debate inside the Trump administration, when they were writing what was called the Nuclear Posture Review, there was a push by some people for the United States to start conducting nuclear explosions again, something that it had not done since the early 1990s. So on the one hand, it’s easy to see this as a kind of straight forward intelligence matter: Are the Russians doing it or are they not?

But on the other hand, there has always been a group of people in the United States who are upset about the test moratorium, and don’t want to see the test ban ratified, and would like the United States to resume nuclear testing. And those people have, since the 1990s, always pointed at the Russians, claiming that they must be doing secret tests and so we should start our own.

And the kind of beautiful irony of this is that when you read articles from Russians who want to start testing –– because, you know, their labs are like ours, they want to do nuclear explosions –– they say, “The Americans are surely getting ready to cheat. So we should go ahead and get ready to go.” So you have these people pointing fingers at one another, but I think the reality is that there are too many people in the United States and Russia who’d be happy to go back to a world in which there was a lot of nuclear testing.

Ariel Conn: And so do we have reason to believe that the Russians might be testing low-yield nuclear weapons or does that still seem to be entirely speculative?

Alex Bell: I’ll let Jeffrey go into some of the historical concerns people have had about the Russian program, but I think it’s important to note that the Russians immediately denied these accusations with the Foreign Minister, Lavrov, actually describing them as delusional and the Deputy Foreign Minister, Sergei Ryabkov, affirmed that they’re in full and absolute compliance with the treaty and the unilateral moratorium on nuclear testing that is also in place until the treaty enters into force. He also penned an op-ed a number of years ago affirming that the Russians believed that any yield on any tests would violate the agreement.

Jeffrey Lewis: Yeah, you know, really from the day the test ban was signed, there have been a group of people in the United States who have argued that the U.S. and Russia have different definitions of zero –– which I don’t find very credible, but it’s a thing people say –– and that the Russians are using this to conduct very small nuclear explosions. This literally was a debate that tore the U.S. Intelligence Community apart during the Clinton administration and these fears led to a really embarrassing moment.

There was a seismic event, some ground motion, some shaking near the Russian nuclear test site in 1997 and the Intelligence Community decided, “Aha, this is it. This is a nuclear test. We’ve caught the Russians,” and Madeline Albright démarched Moscow for conducting a clandestine nuclear test in violation of the CTBT, which it had just signed, and it turned out it was an earthquake out in the ocean.

So there have been a group of people who have been making this claim for more than 20 years. I have never seen any evidence that would persuade me that this is anything other than something they say because they just don’t trust the Russians. I suppose it is possible –– even a stopped watch is right twice a day. But I think before we take any actions, it would behoove us to figure out if there are any facts behind this. Because when you’ve heard the same story for 20 years with no evidence, it’s like the boy who cried wolf. It’s kind of hard to believe

Alex Bell: And that gets back to the sort of strange way that this accusation was framed: not by the Department of State; It’s not clear that Congress has been briefed about it; It’s not clear our allies were briefed about it before Lieutenant General Ashley made these comments. Everything’s been done in a rather unorthodox way and for something as serious as a potential low-yield nuclear test, this really needs to be done according to form.

Jeffrey Lewis: It’s not typical if you’re going to make an accusation that the country is cheating on an arms control treaty to drive a clown car up and then have 15 clowns come out and honk some horns. It makes it harder to accept whatever underlying evidence there may be if you choose to do it in this kind of ridiculous fashion.

Alex Bell: And that would be for any administration, but particularly, an administration that has made a habit of getting out of agreements sort of habitually now.

Jeffrey Lewis: What I loved about the statement that the Defense Intelligence Agency released –– so after the DIA director made this statement, and it’s really worth watching because he reads the statement, which is super inflammatory and there was a reporter in the audience who had been given his remarks in advance. So someone clearly leaked the testimony to make sure there was a reporter there and the reporter asks a question, and then Ashley kind of freaks out and walks back what he said.

So DIA then releases a statement where they double down and say, “No, no, no, he really meant it,” but it starts with the craziest sentence I’ve ever seen, which is “The United States government, including the Intelligence Community, assesses,” which if you know anything about the way the U.S. government works is insane because only the Intelligence Community is supposed to assess. This implies that John Bolton had an assessment, and Mike Pompeo had an assessment, and just the comical manner in which it was handled makes it very hard to take seriously or to see it as anything other than just nakedly partisan assault on the test moratorium and the test ban.

Ariel Conn: So I want to follow up about what the implications are for the test ban, but I want to go back real quick just to some of the technical side of identifying a low-yield explosion. I actually have a background in seismology, so I know that it’s not that big of a challenge for people who study seismic waves to recognize the difference between an earthquake and a blast. And so I’m wondering how small a low yield test actually is. Is it harder to identify, or are there just not seismic stations that the U.S. has access to, or is there something else involved?

Jeffrey Lewis: Well so these are called hydronuclear experiments. They are so incredibly small. They are, on the order in the U.S., there’s something like four pounds of explosive, so basically less explosion than the actual conventional explosions that are used to detonate the nuclear weapon. Some people think the Russians have a slightly bigger definition that might go up to 100 kilograms, but these are mouse farts. They are so small that unless you have the seismic station sitting right next to it, you would never know.

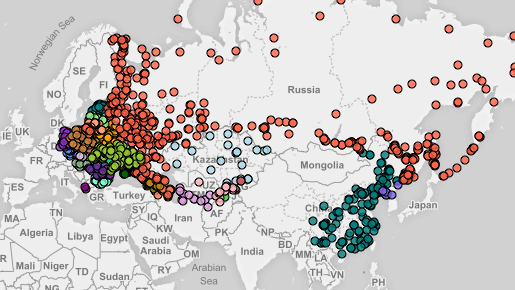

In a way, I think that’s a perfect example of why we’re so skeptical because when the test ban was negotiated, there was this giant international monitoring system put into place. It is not just seismic stations, but it is hydroacoustic stations to listen underwater, infrasound stations to listen for explosions in the air, radionuclide stations to detect any radioactive particles that happen to escape in the event of a test. It’s all of this stuff and it is incredibly sensitive and can detect incredibly small explosions down to about 1,000 tons of explosive and in many cases even less.

And so what’s happened is the allegations against the Russians, every time we have better monitoring and it’s clear that they’re not doing the bigger things, then the allegations are they’re doing ever smaller things. So, again, the way in which it was rolled out was kind of comical and caused us, at least me, to have some doubts about it. It is also the case that the nature of the allegation –– that it’s these tiny, tiny, tiny, tiny experiments, which U.S. scientists, by the way, have said they don’t have any interest in doing because they don’t think they are useful –– it’s almost like the perfect accusation and so that also to me is a little bit suspicious in terms of the motives of the people claiming this is happening.

Alex Bell: I think it’s also important to remember when dealing with verification of treaties, we’re looking for things that would be militarily significant. That’s how we try to build the verification system: that if anybody tried to do anything militarily significant, we’d be able to detect that in enough time to respond effectively and make sure the other side doesn’t gain anything from the violation.

So you could say that experiments like this that our own scientists don’t think are useful are not actually militarily significant, so why are we bringing it up? Do we think that this is a challenge to the treaty overall or do we not like the nature of Russia’s violations? And further, if we’re concerned about it, we should be talking to the Russians instead of about them.

Jeffrey Lewis: I think that is actually the most important point that Alex just made. If you actually think that the Russians have a different definition of zero, then go talk to them and get the same definition. If you think that the Russians are conducting these tests, then talk to the Russians and see if you can get access. If the United States were to ratify the test ban and the treaty were to come into force, there is a provision for the U.S. to ask for an inspection. It’s just a little bit rich to me that the people making this allegation are also the people who refuse to do anything about it diplomatically. If they were truly worried, they’d try to fix the problem.

Ariel Conn: Regarding the fact that the Test-Ban Treaty isn’t technically in force, are a lot of the verification processes still essentially in force anyway?

Alex Bell: The International Monitoring System, as Jeff pointed out, was just sort of in its infancy when the treaty was negotiated and now it’s become this marvel of modern technology capable of detecting tests at even very low yields. And so it is up and running and functioning. It was monitoring the various North Korean nuclear tests that have taken place in this century. It also was doing a lot of additional science like tracking radio particulates that came from the Fukushima disaster back in 2011.

So it is functioning. It is giving readings to any party to the treaty, and it is particularly useful right now to have an independent international source of information of this kind. They specifically did put out a very brief statement following this accusation from the Defense Intelligence Agency saying that they had detected nothing that would indicate a test. So that’s about as far as I think they could get, as far as a diplomatic equivalent of, “What are you talking about?”

Jeffrey Lewis: I Googled it because I don’t remember it off the top of my head, but it’s 321 monitoring stations and 16 laboratories. So the entire monitoring system has been built out and it works far better than anybody thought it would. It’s just that once the treaty comes into force, there will be an additional provision, which is: in the event that the International Monitoring System, or a state party, has any reason to think that there is a violation, that country can request an inspection. And the CTBTO trains to send people to do onsite inspections in the event of something like this. So there is a mechanism to deal with this problem. It’s just that you have to ratify the treaty.

Ariel Conn: So what are the political implications, I guess, of the fact that the U.S. has not ratified this, but Russia has –– and that it’s been, I think you said 23 years? It sounds like the U.S. is frustrated with Russia, but is there a point at which Russia gets frustrated with the U.S.?

Jeffrey Lewis: I’m a little worried about that, yeah. The reality of the situation is I’m not sure that the United States can continue to reap the benefits of this monitoring system and the benefits of what I think Alex rightly described as a global norm against nuclear testing and sort of expect everybody else to restrain themselves while in the United States we refuse to ratify the treaty and talk about resuming nuclear testing.

And so I don’t think it’s a near term risk that the Russians are going to resume testing, but we have seen… We do a lot of work with satellite images at the Middlebury Institute and the U.S. has undertaken a pretty big campaign to keep its nuclear test site modern and ready to conduct a nuclear test on as little as six months’ notice. In the past few years, we’ve seen the Russians do the same thing.

For many years, they neglected their test site. It was in really poor shape and starting in about 2015, they started putting money into it in order to improve its readiness. So it’s very hard for us to say, “Do as we say, not as we do.”

Alex Bell: Yeah, I think it’s also important to realize that if the United States resumes testing, everyone will resume testing. The guardrails will be completely off and that doesn’t make any sense because having the most technologically advanced and capable nuclear weapons infrastructure like we do, we’re benefitted from a global ban on explicit testing. It means we’re sort of locking in our own superiority.

Ariel Conn: So we’re putting that at risk. So I want to expand the conversation from just Russia and the U.S. to pull China in as well because the talk that Ashley gave was also about China’s modernization efforts. And he made some comments that sounded almost like maybe China is considering testing as well. I was sort of curious what your take on his China comments are.

Jeffrey Lewis: I’m going to jump in and be aggressive on this one because my doctoral dissertation was on the history of China’s nuclear weapons program. The class I teach at the Middlebury Institute is one in which we look at declassified U.S. intelligence assessments and then we look at Chinese historical materials in order to see how wrong the intelligence assessments were. This specifically covers U.S. assessments of China’s nuclear testing, and the U.S. just has an awful track record on this topic.

I actually interviewed the former head of China’s nuclear weapons program once, and I was talking to him about this because I was showing him some declassified assessments and I was sort of asking him about, you know, “Had you done this or had you done that?” He sort of kind of took it all in and he just kind of laughed, and he said, “I think many of your assessments were not very accurate.” There was sort of a twinkle in his eye as he said it because I think he was just sort of like, “We wrote a book about it, we told you what we did.”

Anything is possible, and the point of these allegations is events are so small that they are impossible to disprove, but to me, that’s looking at it backwards. If you’re going to cause a major international crisis, you need to come to the table with some evidence, and I just don’t see it.

Alex Bell: The GEM, the Group of Eminent Members, which is an advisory group to the CTBTO, put it best when they said the most effective way to sort of deal with this problem is to get the treaty into force. So we could have intrusive short notice onsite inspections to detect and deter any possible violations.

Jeffrey Lewis: I actually got in trouble, I got to hushed because I was talking to a member and they were trying to work on this statement and they needed the member to come back in.

Ariel Conn: So I guess when you look at stuff like this –– so, basically, all three countries are currently modernizing their nuclear arsenals. Maybe we should just spend a couple minutes talking about that too. What does it mean for each country to be modernizing their arsenal? What does that sort of very briefly look like?

Alex Bell: Nuclear weapons delivery systems, nuclear weapons do age. You do have to maintain them, like you would with any weapon system, but fortunately, from the U.S. perspective, we have exceedingly capable scientists who are able to extend the life of these systems without testing. Jeffrey, if you want to go into what other countries are doing.

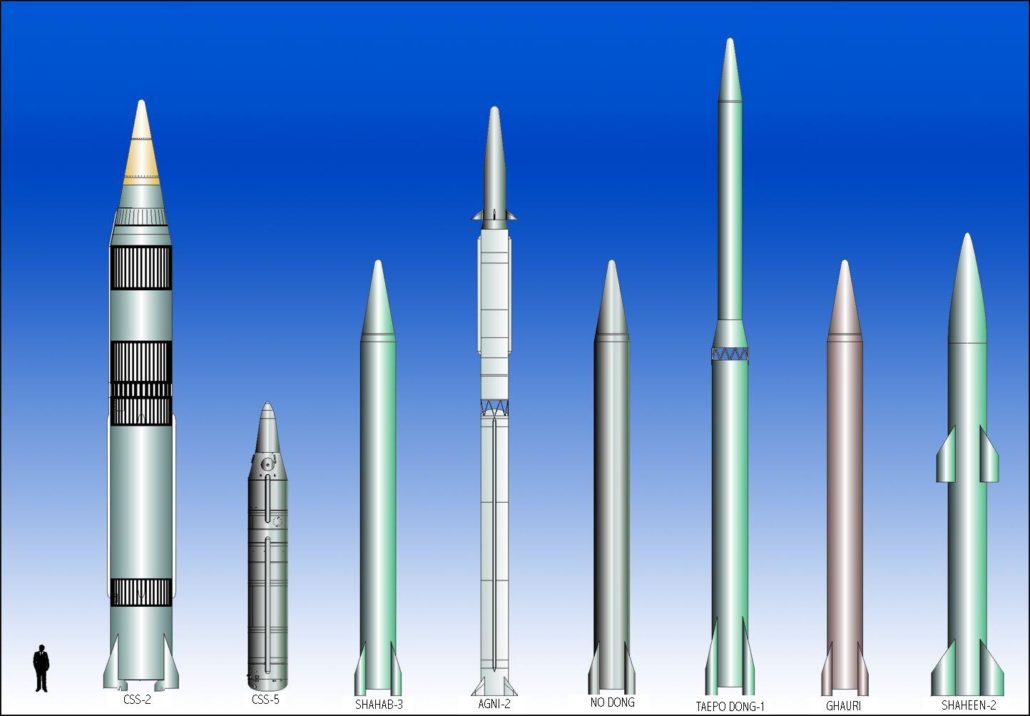

Jeffrey Lewis: Yeah. I think the simplest thing to do is to talk about, at least for the nuclear warheads part, I think as Alex mentioned, all of the countries are building new submarines, and missiles, and bombers that can deliver these nuclear weapons. And that’s a giant enterprise. It costs many billions of dollars every year. But when you actually look at the warheads themselves can tell you what we do in the United States. In some cases, we build new versions of existing designs. In almost all cases, we replace components as they age.

So the warhead design might stay the same, but piece by piece things get replaced. And because we’ve been replacing those pieces over time, if they have to put a new fuse in for a nuclear warhead, they don’t go back and build the ’70s era fuse. They build a new fuse. So even though we say that we’re only replacing the existing components and we don’t try to add new capabilities, in fact, we add new capabilities all the time because as all of these components get better than the weapons themselves get better, and we’re altering the characteristics of the warheads.

So the United States has a warhead on its submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and the Trump administration just undertook a program to give it a capability so that we can turn down the yield. So if we want to make it go off with a very small explosion, they can do that. It’s a full plate of the kinds of changes that are being made, and I think we’re seeing that in Russia and China too.

They are doing all of the same things to preserve the existing weapons they have. They rebuild designs that they have, and I think that they tinker with those designs. And that is constrained somewhat by the fact that there is no explosive testing –– that makes it harder to do those things, which is precisely why we wanted this ban in the first place –– but everybody is playing with their nuclear weapons.

And I think just because there’s a testing moratorium, the scientists who do this, some of them, because they want to go back to nuclear testing or nuclear explosions, they say, “If we could only test with explosions, that would be better.” So there’s even more they want to do, but let’s not act like they don’t get to touch the bombs, because they play with them all the time.

Alex Bell: Yeah. It’s interesting you brought up the low yield option for our submarine-launched ballistic missiles because the House of Representatives actually in the defense appropriations and authorization process that it’s going through right now actually blocked further funding and the deployment of this particular type of warhead because, in their opinion, the President already had plenty low-yield nuclear options, thank you very much. He doesn’t need anymore.

Jeffrey Lewis: Of course, I don’t think this president needs any nuclear options, but-

Alex Bell: But it just shows there’s definitely a political and oversight feature that comes into this modernization debate. The idea that even if the forces that Jeffrey talked about who’ve always wanted to return to testing, even if they could prevail upon a particular administration to go in that direction, it’s unlikely Congress would be as sanguine about it.

Nevada, where our former nuclear testing site is, now the Nevada National Security Site –– it’s not clear that Nevadans are going to be okay with a return to explosive nuclear testing, nor will the people of Utah who sit downwind from that particular site. So there’s actually a “not in my backyard” kind of feature to the debate about further testing.

Jeffrey Lewis: Yeah. The Department of Energy has actually taken… Anytime they do a conventional explosion at the Nevada site, they keep it a secret because they were going to do a conventional explosion 10 or 15 years ago and people got wind of it and were outraged because they were terrified the conventional explosion would kick up a bunch of dust and that there might still be radioactive particulates.

I’m not sure that that was an accurate worry, but I think it speaks to the lack of trust that people around the test site have, given some of the irresponsible things that the U.S. nuclear weapons complex has done over the years. That’s a whole other podcast, but you don’t want to live next to anything that NNSA overseas.

Alex Bell: There’s also a proximity issue. Las Vegas is incredibly close to that facility. Back in the day when they did underground testing there, it used to shake the buildings on the Strip. And Las Vegas has only expanded from 20, 30 years ago, so you’re going to have a lot of people that would be very worried.

Ariel Conn: Yeah. So that’s actually a question that I had. I mean, we have a better idea today of what the impacts of nuclear testing are. Would Americans approve of nuclear weapons being tested on our ground?

Jeffrey Lewis: Probably if they didn’t have to live next to them.

Alex Bell: Yeah. I’ve been to some of the states where we conducted tests other than Nevada. So Colorado, where we tried to do this brilliant idea of whether we could do fracking via nuclear explosion. You can see the problems inherent in that idea. Alaska, New Mexico, obviously, where the first nuclear test happened. We also tested weapons in Mississippi. So all of these states have been affected in various ways and radio particulates from the sites in Nevada have drifted as far away from Maine, and scientists have been able to trace cancer clusters half a continent away.

Jeffrey Lewis: Yeah, I would add that –– Alex mentioned testing in Alaska –– so there was a giant test in 1971 in Alaska called Cannikin. It was five megatons. So a megaton is 1,000 kilotons. Hiroshima was 20 kilotons and it really made some Canadians angry and the consequence of the angry Canadians was they founded Greenpeace. So the whole iconic Greenpeace on a boat was originally driven by a desire to stop U.S. nuclear testing in Alaska. So, you know, people get worked up.

Ariel Conn: Do you think someone in the U.S. is actively trying to bring testing back? Do you think that we’re going to see more of this or do you think this might just go away?

Jeffrey Lewis: Oh yeah. There was a huge debate at the beginning of the Trump administration. I actually wrote this article making fun of Rick Perry, the Secretary of Energy, who I have to admit has turned out to be a perfectly normal cabinet secretary in an administration that looks like the Star Wars Cantina.

Alex Bell: It’s a low bar.

Jeffrey Lewis: It’s a low bar, and maybe just barely, but Rick got over it. But I was sort of mocking him and the article was headlined, “Even Rick Perry isn’t dumb enough to resume nuclear testing,” and I got notes, people saying, “This is not funny. This is a serious possibility.” So, yeah, I think there has long been a group of people who did not want to end testing. U.S. labs refuse to prepare for the end of testing. So when the U.S. stopped, it was Congress just telling them to stop. They have always wanted to go back to testing, and these are the same people I think who are accusing the Russians of doing things, I think as much so that they can get out of the test ban as anything else.

Alex Bell: Yeah, I would agree with that assessment. Those people have always been here. It’s strange to me because most scientists have affirmed that we know more about our nuclear weapons now not blowing them up than we did before because of the advanced computer modeling, technological advances of the Stockpile Stewardship program, which is the program that extends the life of these warheads. They get to do a lot of great science, and they’ve learned a lot of things about our nuclear forces that we didn’t know before.

So it’s hard to make a case that it is absolutely necessary or would ever be absolutely necessary to return to testing. You would have to totally throw out our obligations that we have to things like the nuclear non-proliferation treaty, which is to pursue the cessation of an arms race in good faith, and a return to testing I think would not be very good faith.

Ariel Conn: Maybe we’ve sort of touched on this, but I guess it’s still not clear to me. Why would we want to return to testing? Especially if, like you said, the models are so good?

Jeffrey Lewis: I think you have to approach that question like an anthropologist. Because some countries are quite happy living under a test ban for exactly the reason that you pointed out, that they are getting all kinds of money to do all kinds of interesting science. And so Chinese seem pretty happy about it; The UK, actually –– I’ve met some UK scientists who are totally satisfied with it.

But I think the culture in the U.S. laboratories, which had really nothing to do with the reliability of the weapons and everything to do with the culture of the lab, was like the day that a young designer became a man or a woman was the day that person’s design went out into the desert and they had to stand there and be terrified it wasn’t going to work, and then feel the big rumble. So I think there are different ways of doing science. I think the labs in the United States were and are sentimentally attached to solving these problems with explosions.

Alex Bell: There’s also sort of a strange desire to see them. My first trip out to the test site, I was the only woman on the trip and we were looking at the Sedan Crater, which is just this enormous crater from an explosion underground that was much bigger than we thought it was going to be. It made this, I think it’s seven football fields across, and to me, it was just sort of horrifying, and I looked at it with dread. And a lot of the people who were on the trip reacted entirely differently with, “I thought it would be bigger,” and, “Wouldn’t it be awesome to see one of these go off, just once?” and had a much different take on what these tests were for and what they sort of indicated.

Ariel Conn: So we can actually test nuclear weapons without exploding them. Can you talk about what the difference is between testing and explosions, and what that means?

Jeffrey Lewis: The way a nuclear weapon works is you have a sphere of fissile material –– so that’s plutonium or highly enriched uranium –– and that’s surrounded by conventional explosives. And around that, there are detonators and electronics to make sure that the explosives all detonate at the exact same moment so that they spherically compress or implode the plutonium or highly enriched uranium. So when it gets squeezed down, it makes a big bang, and then if it’s a thermonuclear weapon, then there’s something called a secondary, which complicates it.

But you can do that –– you can test all of those components, just as long as you don’t have enough plutonium or highly enriched uranium in the middle to cause a nuclear explosion. So you can fill it with just regular uranium, which won’t go critical, and so you could test the whole setup that way for all of the things in a nuclear weapon that would make it a thermonuclear weapon. There’s a variety of different fusion research techniques you can do to test those kinds of reactions.

So you can really simulate everything, and you can do as many computer simulations as you want, it’s just that you can’t put it all together and get the big bang. And so the U.S. has built this giant facility at Livermore called NIF, the National Ignition Facility, which is a many billion-dollar piece of equipment, in order to sort of simulate some of the fusion aspects of a nuclear weapon. It’s an incredible piece of equipment that has taught U.S. scientists far more than they ever knew about these processes when they were actually exploding things. It’s far better for them, and they can do that. It’s completely legal.

Alex Bell: Yeah, the most powerful computer in the world belongs to Los Alamos. Its job is to help simulate these nuclear explosions and process data related to the nuclear stockpile.

Jeffrey Lewis: Yeah, I got a kick –– I always check in on that list, and it’s almost invariably one of the U.S. nuclear laboratories that has the top computer. And then one time I noticed that the Chinese had jumped up there for a minute and it was their laboratory.

Alex Bell: Yup, it trades back and forth.

Jeffrey Lewis: Good times.

Alex Bell: A lot of the data that goes into this is observational information and technical readings that we got from when we did explosive testing. And our testing record is far more extensive than any other country, which is one of the reasons why we have sort of this advantage that would be locked in, in the event of a CTBT entering into force.

Ariel Conn: Yeah, I thought that was actually a really interesting point. I don’t know if there’s more to elaborate on it, but the idea that the U.S. could actually sacrifice some of its nuclear superiority by ––

Alex Bell: Returning to testing?

Ariel Conn: Yeah.

Alex Bell: Yeah, because if we go, everyone goes.

Ariel Conn: There were countries that still weren’t thrilled even with the testing that is allowed. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

Alex Bell: Yes. A lot of countries, particularly the countries that back the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which is a new treaty that does not have any nuclear weapon states as a part of it, but it’s a total ban on the possession and use of nuclear weapons, and those countries are particularly frustrated with what they see as the slow pace of disarmament by the nuclear weapon states.

The Nonproliferation Treaty, which is sort of the glue that holds all this together, was indefinitely extended back in 1995. The price for that from the non-nuclear weapon states was the commitment of nuclear weapon states to sign and ratify a comprehensive test ban. So 25 years later almost, they’re still waiting.

Ariel Conn: I will add that, I think as of this week, I believe three of the United States –– California, New Jersey and Oregon –– have passed resolutions supporting the U.S. joining the treaty that actually bans nuclear weapons, that recent one.

Alex Bell: Yeah. It’s been interesting, while it’s something that the verification measures –– Jeffrey might have some thoughts on this too –– to me, principles aside, the verification measures in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons makes it sort of an unviable treaty. But from a messaging perspective, you’re seeing kind of the first time since the Cold War where citizenry around the world is saying, “You have to get rid of these weapons. They’re no longer acceptable. They’ve become liabilities, not assets.”

So while I don’t think the treaty itself is a workable treaty for the United States, I think that the sentiment behind it is useful in persuading leaders that we do need to do more on disarmament.

Jeffrey Lewis: I would just say that I think just like we saw earlier, there’s a lot of the U.S. wanting to have its cake and eat it too. And so the Nonproliferation Treaty, which is the big treaty that says, “Countries should not be able to acquire nuclear weapons,” it also commits the United States and the other nuclear powers to work toward disarmament. That’s not something they take seriously.

Just like with nuclear testing where you see this, “Oh, well, maybe we could edge back and do it,” you see the same thing just on disarmament issues generally. So having people out there who are insisting on holding the most powerful countries to account to make sure that they do their share, I also think is really important.

Ariel Conn: All right. So I actually think that’s sort of a nice note to end on. Is there anything else that you think is important that we didn’t get into or that just generally is important for people to know?

Alex Bell: I would just reiterate the point that if the U.S. government is truly concerned that Russia is conducting tests at even very low yields, that we need to be engaged in a conversation with them, that a global ban on nuclear explosive testing is good for every country in this world and we shouldn’t be doing things to derail the pursuit of such a treaty.

Ariel Conn: Agreed. All right, well, thank you both so much for joining today.

As always, if you’ve been enjoying the podcast, please take a moment to like it, share it, and maybe even leave a good review and I will be back again next month with another episode of the FLI Podcast.