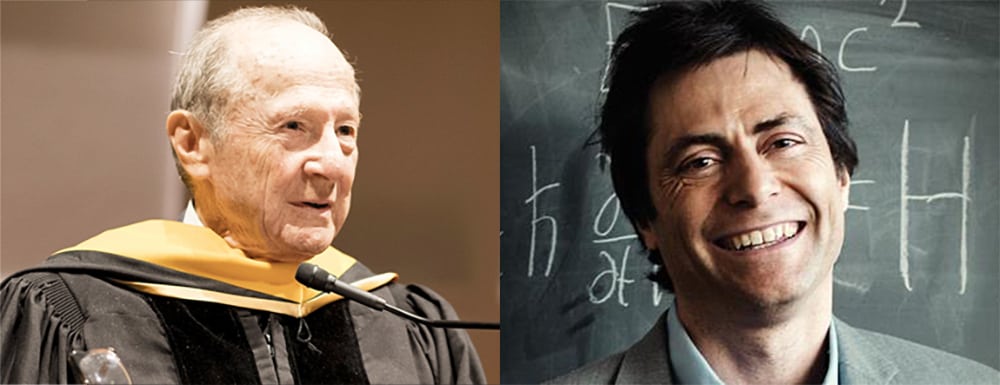

In this special two-part podcast Ariel Conn is joined by Max Tegmark for a conversation with Dr. Matthew Meselson, biologist and Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences at Harvard University. Dr. Meselson began his career with an experiment that helped prove Watson and Crick’s hypothesis on the structure and replication of DNA. He then got involved in arms control, working with the US government to renounce the development and possession of biological weapons and halt the use of Agent Orange and other herbicides in Vietnam. From the cellular level to that of international policy, Dr. Meselson has made significant contributions not only to the field of biology, but also towards the mitigation of existential threats.

In Part One, Dr. Meselson describes how he designed the experiment that helped prove Watson and Crick’s hypothesis, and he explains why this type of research is uniquely valuable to the scientific community. He also recounts his introduction to biological weapons, his reasons for opposing them, and the efforts he undertook to get them banned. Dr. Meselson was a key force behind the U.S. ratification of the Geneva Protocol, a 1925 treaty banning biological warfare, as well as the conception and implementation of the Biological Weapons Convention, the international treaty that bans biological and toxin weapons.

Topics discussed in this episode include:

- Watson and Crick’s double helix hypothesis

- The value of theoretical vs. experimental science

- Biological weapons and the U.S. biological weapons program

- The Biological Weapons Convention

- The value of verification

- Future considerations for biotechnology

Publications and resources discussed in this episode include:

Click here for Part 2: Anthrax, Agent Orange, and Yellow Rain: Verification Stories with Matthew Meselson and Max Tegmark

Ariel: Hi everyone and welcome to the FLI podcast. I’m your host, Ariel Conn with the Future of Life Institute, and I am super psyched to present a very special two-part podcast this month. Joining me as both a guest and something of a co-host is FLI president and MIT physicist Max Tegmark. And he’s joining me for these two episodes because we’re both very excited and honored to be speaking with Dr. Matthew Meselson. Matthew not only helped prove Watson and Crick’s hypothesis about the structure of DNA in the 1950s, but he was also instrumental in getting the U.S. to ratify the Geneva Protocol, in getting the U.S. to halt its Agent Orange Program, and in the creation of the Biological Weapons Convention. He is currently Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences at Harvard University where, among other things, he studies the role of sexual reproduction in evolution. Matthew and Max, thank you so much for joining us today.

Matthew: A pleasure.

Max: Pleasure.

Ariel: Matthew, you’ve done so much and I want to make sure we can cover everything, so let’s just dive right in. And maybe let’s start first with your work on DNA.

Matthew: Well, let’s start with my being a graduate student at Caltech.

Ariel: Okay.

Matthew: I had a been a freshman at Caltech but I didn’t like it. The teaching at that time was by rote except for one course, which was Linus Pauling’s course, General Chemistry. I took that course and I did a little research project for Linus, but I decided to go to graduate school much later at the University of Chicago because there was a program there called Mathematical Biophysics. In those days, before the structure of DNA was known, what could a young man do who liked chemistry and physics but wanted to find out how you could put together the atoms of the periodic chart and make something that’s alive?

There was a unit there called Mathematical Biophysics and the head of it was a man with a great big black beard, and that all seemed very attractive to a kid. So, I decided to go there but because of my freshman year at Caltech I got to know Linus’ daughter, Linda Pauling, and she invited me to a swimming pool party at their house in Sierra Madre. So, I’m in the water. It’s a beautiful sunny day in California, and the world’s greatest chemist comes out wearing a tie and a vest and looks down at me in the water like some kind of insect and says, “Well, Matt, what are you going to do next summer?”

I looked up and I said, “I’m going to the University of Chicago to Nicolas Rashevsky” — that’s the man with the black beard. And Linus looked down at me and said, “But Matt, that’s a lot of baloney. Why don’t you come be my graduate student?” So, I looked up and said, “Okay.” That’s how I got into graduate school. I started out in X-ray crystallography, a project that Linus gave me to do. One day, Jacques Monod from the Institut Pasteur in Paris came to give a lecture at Caltech, and the question then was about the enzyme beta-galactosidase, a very important enzyme because studies of the induction of that enzyme led to the hypothesis of messenger RNA, also how genes are turned on and off. A very important protein used for those purposes.

The question of Monod’s lecture was: is this protein already lurking inside of cells in some inactive form? And when you add the chemical that makes it be produced, which is lactose (or something like lactose), you just put a little finishing touch on the protein that’s lurking inside the cells and this gives you the impression that the addition of lactose (or something like lactose) induces the appearance of the enzyme itself. Or the alternative was maybe the addition to the growing medium of lactose (or something like lactose) causes de novo production, a synthesis of the new protein, the enzyme beta-galactosidase. So, he had to choose between these two hypotheses. And he proposed an experiment for doing it — I won’t go into detail — which was absolutely horrible and would certainly not have worked, even though Jacques was a very great biologist.

I had been taking Linus’ course on the nature of the chemical bond, and one of the key take-home problems was: calculate the ratio of the strength of the Deuterium bond to the Hydrogen bond. I found out that you could do that in one line based on the — what’s called the quantum mechanical zero point energy. That impressed me so much that I got interested in what else Deuterium might have about it that would be interesting. Deuterium is heavy Hydrogen, with a neutron in the nucleus. So, I thought: what would happen if you exchange the water in something alive with Deuterium? And I read that there was a man who tried to do that with a mouse, but that didn’t work. The mouse died. Maybe because the water wasn’t pure, I don’t know.

But I had found a paper that you could grow bacteria, Escherichia coli, in pure heavy water with other nutrients added but no light water. So, I knew that you could make DNA from that as you could probably make DNA or also beta-galactosidase a little heavier by having it be made out of heavy Hydrogen rather than light. There’s some intermediate details here, but at some point I decided to go see the famous biophysicist Max Delbrück. I was in the Chemistry Department and Max was in the Biology Department.

And there was, at that time, a certain — I would say not a barrier, but a three-foot fence between these two departments. Chemists looked down on the biologists because they worked just with squiggly, gooey things. Then the physicists naturally looked down on the chemists and the mathematicians looked down on the physicists. At least that was the impression of us graduate students. So, I was somewhat fearsome to go meet Max Delbrück, and he also had a fearsome reputation, as not tolerating any kind of nonsense. But finally I went to see him — he was a lovely man actually — and the first thing he said when I sat down was, “What do you think about these two new papers of Watson and Crick?” I said I’d never heard about them. Well, he jumped out of his chair and grabbed a heap of reprints that Jim Watson had sent to him, and threw them all at me, and yelled at me, and said, “Read these and don’t come back until you read them.”

Well, I heard the words “come back.” So I read the papers and I went back, and he explained to me that there was a problem with the hypothesis that Jim and Francis had for DNA replication. The idea of theirs was that the two strands come apart by unwinding the double helix. And if that meant that you had to unwind the entire parent double helix along its whole length, the viscous drag would have been impossible to deal with. You couldn’t drive it with any kind of reasonable biological motor.

So Max thought that you don’t actually unwind the whole thing: You make breaks, and then with little pieces you can unwind those and then seal them up. This gives you a kind of dispersive replication in which the two daughter molecules, each one has some pieces of the parent molecule but no complete strand from the parent molecule. Well, when he told me that, I almost immediately — I think it was almost immediately — realized that density separation would be a way to find out if this hypothesis predicted the finding of half heavy DNA after one generation. That is, one old strand together with one new strand forming one new duplex of DNA.

So I went to Linus Pauling and said, “I’d like to do that experiment,” and he gently said, “Finish your X-ray crystallography.” So, I didn’t do that experiment then. Instead I went to Woods Hole to be a teaching assistant in the Physiology course with Jim Watson. Jim had been living at Caltech that year in the faculty club, the Athenaeum, and so had I, so I had gotten to know Jim pretty well then. So there I was at Woods Hole, and I was not really a teaching assistant — I was actually doing an experiment that Jim wanted me to do — but I was meeting with the instructors.

One day we were on the second floor of the Lily building and Jim looked out the window and pointed down across the street. Sitting on the grass was a fellow, and Jim said, “That guy thinks he’s pretty smart. His name is Frank Stahl. Let’s give him a really tough experiment to do all by himself.” The Hershey–Chase Experiment. Well, I knew what that experiment was, and I didn’t think you could do it in one day, let alone just single-handedly. So I went downstairs to tell this poor Frank Stahl guy that they were going to give him a tough assignment.

I told him about that, and I asked him what he was doing. And he was doing something very interesting with bacteriophages. He asked me what I was doing, and I told him that I was thinking of finding out if DNA replicates semi-conservatively the way Watson and Crick said it should, by a method that would have something to do with density measurements in a centrifuge. I had no clear idea how to do that, just something by growing cells in heavy water and then switching them to light water and see what kind of DNA molecules they made in a density gradient in a centrifuge. And Frank made some good suggestions, and we decided to do this together at Caltech because he was coming to Caltech himself to be a postdoc that very next September.

Anyway, to make a long story short we made the experiment work, and we published it in 1958. That experiment said that DNA is made up of two subunits and when it replicates its subunits come apart, each one becomes associated with a new sub-unit. Now anybody in his right mind would have said, “By sub-unit you really mean a single polynucleotide chain. Isn’t that what you mean?” And we would have answered at that time, “Yes of course, that’s what we mean, but we don’t want to say that because our experiment doesn’t say that. Our experiment says that some kind of subunits do that — the subunits almost certainly are the single polynucleotide chains — but we want to confine our written paper to only what can be deduced from the experiment itself, and not go one inch beyond that.” It was later a fellow named John Cairns proved that the subunits were really the single polynucleotide chains of DNA.

Ariel: So just to clarify, those were the strands of DNA that Watson and Crick had predicted, is that correct?

Matthew: Yes, it’s the result that they would have predicted, exactly so. We did a bunch of other experiments at Caltech, some on mutagenesis and other things, but this experiment, I would say, had a big psychological value. Maybe its psychological value was more than anything else.

The year 1954, the year after Watson and Crick had published the structure of DNA and their speculations as to its biological meaning at Woods Hole, and Jim was there and Francis was there. I was there, as I mentioned. Rosalind Franklin was there. Sydney Brenner was there. It was very interesting because a good number of people there didn’t believe their structure for DNA, or that it had anything to do with life and genes, on the grounds that it was too simple, and life had to be very complicated. And the other group of people thought it was too simple to be wrong.

So two views: every one agreed that the structure that they had proposed was a simple one. Some people thought simplicity meant truth, and others thought that in biology, truth had to be complicated. What I’m trying to get at here is that after the structure was published it was just a hypothesis. It wasn’t proven by any methods of, for example, crystallography, to show — it wasn’t until much later that crystallography and a certain other kind of experiment actually proved that the Watson and Crick structure was right. At that time, it was a proposal based on model building.

So why was our experiment, the experiment showing the semi-conservative replication, of psychological value? It was because this is the first time you could actually see something. Namely, bands in an ultracentrifuge gradient. So, I think the effect of our experiment in 1958 was to make the DNA structure proposal of 1954 — it gave it a certain reality. Jim, in his book The Double Helix, actually says that he was greatly relieved when that came along. I’m sure he believed the structure was right all the time, but this certainly was a big leap forward in convincing people.

Ariel: I’d like to pull Max into this just a little bit and then we’ll get back to your story. But I’m really interested in this idea of the psychological value of science. Sort of very, very broadly, do you think a lot of experiments actually come down to more psychological value, or was your experiment unique in that way? I thought that was just a really interesting idea. And I think it would be interesting to hear both of your thoughts on this.

Matthew: Max, where are you?

Max: Oh, I’m just fascinated by what you’ve been telling us about here. I think of course, the sciences — we see again and again that experiments without theory and theory without experiments, neither of them would be anywhere near as amazing as when you have both. Because when there’s a really radical new idea put forth, half the time people at the time will dismiss it and say, “Oh, that’s obviously wrong,” or whatnot. And only when the experiment comes along do people start taking it seriously and vice versa. Sometimes a lot of theoretical ideas are just widely held as truths — like Aristotle’s idea of how the laws of motion should be — until somebody much later decides to put it to the experimental test.

Matthew: That’s right. In fact, Sir Arthur Eddington is famous for two things. He was one of the first ones to find experimental proof of the accuracy of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, and the other thing for which Eddington was famous was having said, “No experiment should be believed until supported by theory.”

Max: Yeah. Theorists and experiments have had this love-hate relationship throughout the ages, which I think, in the end, has been a very fruitful relationship.

Matthew: Yeah. In cosmology the amazing thing to me is that the experiments now cost billions or at least hundreds of millions of dollars. And that this is one area, maybe the only one, in which politicians are willing to spend a lot of money for something that’s so beautiful and theoretical and far off and scientifically fundamental as cosmology.

Max: Yeah. Cosmology is also a reminder again of the importance of experiment, because the big questions there — such as where did everything come from, how big is our universe, and so on — those questions have been pondered by philosophers and deep thinkers for as long as people have walked the earth. But for most of those eons all you could do was speculate with your friends over some beer about this, and then you could go home, because there was no further progress to be made, right?

It was only more recently when experiments gave us humans better eyes: where with telescopes, et cetera, we could start to see things that our ancestors couldn’t see, and with this experimental knowledge actually start to answer a lot of these things. When I was a grad student, we argued about whether our universe was 10 billion years old or 20 billion years old. Now we argue about whether it’s 13.7 or 13.8 billion years old. You know why? Experiment.

Matthew: And now is a more exciting time than any previous time, I think, because we’re beginning to talk about things like multi-universes and entanglement, things that are just astonishing and really almost foreign to the way that we’re able to think — that there’s other universes, or that there could be what’s called quantum mechanical entanglement: that things influence each other very far apart, so far apart that light could not travel between them in any reasonable time, but by a completely weird process, which Einstein called spooky action at a distance. Anyway, this is an incredibly exciting time about which I know nothing except from podcasts and programs like this one.

Max: Thank you for bringing this up, because I think the examples you gave right now actually are really, really linked to these breakthroughs in biology that you were telling us about, because I think we’ve been on this intellectual journey all along where we humans kept underestimating our ability to understand stuff. So for the longest time, we didn’t even really try our best because we assumed it was futile. People used to think that the difference between a living bug and a dead bug was that there was some sort of secret sauce, and the living bug has some sort life essence or something that couldn’t be studied with the tools of science. And then by the time people started to take seriously that maybe actually the difference between that living bug and the dead bug is that the mechanism is just broken in one of them, and you can study the mechanism — then you get to these kind of experimental questions that you were talking about. I think in the same way, people had previously shied away from asking questions about, not just about life, but about the origin of our universe for example, as being always hopelessly beyond where we were ever even able to do anything about, so people didn’t ask what experiments they could make. They just gave up without even trying.

And then gradually I think people were emboldened by breakthroughs in, for example, biology, to say, “Hey, what about — let’s look at some of these other things where people said we’re hopeless, too?” Maybe even our universe obeys some laws that we can actually set out to study. So hopefully we’ll continue being emboldened, and stop being lazy, and actually work hard on asking all questions, and not just give up because we think they’re hopeless.

Matthew: I think the key to making this process begin was to abandon supernatural explanations of natural phenomena. So long as you believe in supernatural explanations, you can’t get anywhere, but as soon as you give them up and look around for some other kind of explanation, then you can begin to make progress. The amazing thing is that we, with our minds that evolved under conditions of hunter-gathering and even earlier than that — that these minds of ours are capable of doing such things as imagining general relativity or all of the other things.

So is there any limit to it? Is there going to be a point beyond which we will have to say we can’t really think about that, it’s too complicated? Yes, that will happen. But we will by then have built computers capable of thinking beyond. So in a sense, I think once supernatural thinking was given up, the path was open to essentially an infinity of discovery, possibly with the aid of advanced artificial intelligence later on, but still guided by humans. Or at least by a few humans.

Max: I think you hit the nail on the head there. Saying, “All this is supernatural,” has been used as an excuse to be lazy over and over again, even if you go further back, you know, hundreds of years ago. Many people looked at the moon, and they didn’t ask themselves why the moon doesn’t fall down like a normal rock because they said, “Oh, there’s something supernatural about it, earth stuff obeys earth laws, heaven stuff obeys heaven laws, which are just different. Heaven stuff doesn’t fall down.”

And then Newton came along and said, “Wait a minute. What if we just forget about the supernatural, and for a moment, explore the hypothesis that actually stuff up there in the sky obeys the same laws of physics as the stuff on earth? Then there’s got to be a different explanation for why the moon doesn’t fall down.” And that’s exactly how he was led to his law of gravitation, which revolutionized things of course. I think again and again, there was again the rejection of supernatural explanations that led people to work harder on understanding what life really is, and now we see some people falling into the same intellectual trap again and saying, “Oh yeah, sure. Maybe life is mechanistic but intelligence is somehow magical, or consciousness is somehow magical, so we shouldn’t study it.”

Now, artificial intelligence progress is really, again, driven by people willing to let go of that and say, “Hey, maybe intelligence is not supernatural. Maybe it’s all about information processing, and maybe we can study what kind of information processing is intelligent and maybe even conscious as in having experiences.” There’s a lot learn at this meta level from what you’re saying there, Matthew, that if we resist excuses to not do the work by saying, “Oh, it’s supernatural,” or whatever, there’s often real progress we can make.

Ariel: I really hate to do this because I think this is such a great discussion, but in the interest of time, we should probably get back to the stories at Harvard, and then you two can discuss some of these issues — or others — a little more shortly in this interview. So yeah, let’s go back to Harvard.

Matthew: Okay, Harvard. So I came to Harvard. I thought I’d stay only five years. I thought it was kind of a duty for an American who’d grown up in the West to find out a little bit about what the East was like. But I never left. I’ve been here for 60 years. When I was here for about three years, my friend Paul Doty, a chemist, no longer living, asked me if I’d like to go work at the United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency in Washington DC. He was on the general advisory board of that government branch, and it was embedded in the State Department building on 21st Street in Washington, but it was quite independent, it could report it directly to the White House, and it was the first year of its existence, and it was trying to find out what it should be doing.

And one of the ways it tried to find out what it should be doing was to hire six academics to come just for the summer. One of them was me, one of them was Freeman Dyson, the physicist, and there were four others. When I got there, they said, “Okay, you’re going to work on theater nuclear weapons arms control,” something I knew less than zero about. But I tried, and I read things and so on, and very famous people came to brief me — like Llewellyn Thompson, our ambassador to Moscow, and Paul Nitze, the deputy secretary of defense.

I realized that I knew nothing about this and although scientists often have the arrogance to think that they can say something useful about nearly anything if they think about it, here was something that so many people had thought about. So I went through my boss and said, “Look, you’re wasting your time and your money. I don’t know anything about this. I’m not gonna produce anything useful. I’m a chemist and a biologist. Why don’t you have me look into the arms control of that stuff?” He said, “Yeah, you could do whatever you want. We had a guy who did that, and he got very depressed and he killed himself. You could have his desk.”

So I decided to look into chemical and biological weapons. In those days, the arms control agency was almost like a college. We all had to have very high security clearances, and that was because the congress was worried that maybe there would be some leakers amongst the people doing this suspicious work in arms control, and therefore, we had to be in possession of the highest level of security clearance. This had, in a way, the unexpected effect that you could talk to your neighbor about anything. Ordinarily, you might not have clearance for what your neighbor, a different office, a different room, or a different desk was doing — but we had, all of us, such security clearances that we could all talk to each other about what we were doing. So it was like a college in that respect. It was a wonderful atmosphere.

Anyway, I decided I would just focus on biological weapons, because the two together would be too much for a summer. I went to the CIA, and a young man there showed me everything we knew about what other countries were doing with biological weapons, and the answer was we knew very little. Then I went to Fort Detrick to see what we were doing with biological weapons, and I was given a tour by a quite good immunologist who had been a faculty member at the Harvard Medical School, name was Leroy Fothergill. And we came to a big building, seven stories high. From a distance, you would think it had windows but when you get up close, they were phony windows. And I asked Dr. Fothergill, “What do we do in there?” He said, “Well, we have a big fermentor in there and we make Anthrax.” I said, “Well, why do we do that?” He said, “Well, biological weapons are a lot cheaper than nuclear weapons. It will save us money.”

I don’t think it took me very long, certainly by the time I got back to my office in the State Department Building, to realize that hey, we don’t want devastating weapons of mass destruction to be really cheap and save us money. We would like them to be so expensive that no one can afford them but us, or maybe no one at all. Because in the hands of other people, it would be like their having nuclear weapons. It’s ridiculous to want a weapon of mass destruction that’s ultra-cheap.

So that dawned on me. My office mate was Freeman Dyson, and I talked with him a little bit about it and he encouraged me greatly to pursue this. The more I thought about it, two things motivated me very strongly. Not just the illogic of it. The illogic of it motivated me only in the respect that it made me realize that any reasonable person could be convinced of this. In other words, it wouldn’t be a hard job to get this thing stopped, because anybody who’s thoughtful would see the argument against it. But there were two other aspects. One, it was my science: biology. It’s hard to explain, but that my science would be perverted in that way. But there’s another aspect, and that is the difference between war and peace.

We’ve had wars and we’ve had peace. Germany fights Britain, Germany is aligned with Britain. Britain fights France, Britain is aligned with France. There’s war. There’s peace. There are things that go on during war that might advance knowledge a little bit, but certainly, it’s during times of peace that the arts, the humanities, and science, too, make great progress. What if you couldn’t tell the difference and all the time is both war and peace? By that I mean, war up until now has been very special. There are rules of it. Basically, it starts with hitting a guy so hard that he’s knocked out or killed. Then you pick up a stone and hit him with that. Then you make a spear and spear him with that. Then you make a bow and arrow and spear him with that. Then later on, you make a gun and you shoot a bullet at him. Even a nuclear weapon: it’s all like hitting with an arm, and furthermore, when it stops, it’s stopped, and you know when it’s going on. It make sounds. It makes blood. It makes bang.

Now biological weapons, they could be responsible for a kind of war that’s totally surreptitious. You don’t even know what’s happening, or you know it’s happening but it’s always happening. They’re trying to degrade your crops. They’re trying to degrade your genetics. They’re trying to introduce nasty insects to you. In other words, it doesn’t have a beginning and an end. There’s no armistice. Now today, there’s another kind of weapon. It has some of those attributes: It’s cyber warfare. It might over time erase the distinction between war and peace. Now that really would be a threat to the advance of civilization, a permanent science fiction-like, locked in, war-like situation, never ending. Biological weapons have that potentiality.

So for those two reasons — my science, and it could erase the distinction between war and peace, could even change what it means to be human. Maybe you could change what the other guy’s like: change his genes somehow. Change his brain by maybe some complex signaling, who knows? Anyway, I felt a strong philosophical desire to get this thing stopped. Fortunately, I was in Harvard University, and so was Jack Kennedy. And although by that time he had been assassinated, he had left behind lots of people in the key cabinet offices who were Kennedy appointees. In particular, people who came from Harvard. So I could knock on almost any door.

So I went to Lyndon Johnson’s national security adviser, who had been Jack Kennedy’s national security adviser, and who had been the dean at Harvard who hired me, McGeorge Bundy, and said all these things I’ve just said. And he said, “Don’t worry, Matt, I’ll keep it out of the war plans.” I’ve never seen a war plan, but I guess if he said that, it was true. But that didn’t mean it wouldn’t keep on being developed.

Now here I should make an aside. Does that mean that the Army or the Navy or the Air Force wanted these things? No. We develop weapons in a kind of commercial way that is a part of the military. In this case, the Army Materiel Command works out all kinds of things: better artillery pieces, communication devices, and biological weapons. It doesn’t belong to any service. Then after, in this case, biological weapons, if the laboratories develop what they think is a good biological weapon, they still have to get one of the services — Air Force, Army, Navy, Marines — to say, “Okay, we’d like that. We’ll buy some of that.”

There was always a problem here. Nobody wanted these things. The Air Force didn’t want them because you couldn’t calculate how many planes you needed to kill a certain number of people. You couldn’t calculate the human dose response, and beyond that you couldn’t calculate the dose that would reach the humans. There were too many unknowns. The Army didn’t like it, not only because they, too, wanted predictability, but because their soldiers are there, maybe getting infected by the same bugs. Maybe there’s vaccines and all that, but it also seemed dishonorable. The Navy didn’t want it because the one thing that ships have to be is clean. So oddly enough, biological weapons were kind of a step child.

Nevertheless, there was a dedicated group of people who really liked the idea and pushed hard on it. These were the people who were developing the biological weapons, and they had their friends in Congress, so they kept getting it funded. So I made a kind of a plan, like a protocol for doing an experiment, to get us to stop all this. How do you do that? Well, first you ask yourself: who can stop it? There’s only one person who can stop it. That’s the President of the United States.

The next thing is: what kind of advice is he going to get, because he may want to do something, but if all the advice he gets is against it, it takes a strong personality to go against the advice you’re getting. Also, word might get out, if it turned out you made a mistake, that they told you all along it was a bad idea and you went ahead anyway. That makes you a super fool. So the answer there is: well, you go to talk to the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of State, and the head of the CIA, and all of the senior people, and their people who are just below them.

Then what about the people who are working on the biological weapons? You have to talk to them, but not so much privately, because they really are dedicated. There were some people who are caught in this and really didn’t want to be doing it, but there were other people who were really pushing it, and it wasn’t possible, really, to tell them to quit your job and get out of this. But what you could do is talk with them in public, and by knowing more than they knew about their own subject — which meant studying up a lot — show that they were wrong.

So I literally crammed, trying to understand everything there was to know about aerobiology, diffusion of clouds, pathogenicity, history of biological weapons, the whole bit, so that I could sound more knowledgeable. I know that’s a sort of slightly underhanded way to win an argument, but it’s a way of convincing the public that the guys who are doing this aren’t so wise. And then you have to get public support.

I had a pal here who told me I had to go down to Washington and meet a guy named Howard Simons, who was the managing editor of the Washington Post. He had been a science journalist at The Post and that’s why some scientists up here in Harvard knew him. So, I went down there — Howie at that time was now managing editor — and I told him, “I want to get newspaper articles all over the country about the problem of biological weapons.” He took out a big yellow pad and he wrote down about 30 names. He said, “These are the science journalists at San Francisco Chronicle, Baltimore Sun, New York Times, et cetera, et cetera.” Put down the names of all the main science journalists. And he said to me, “These guys have to have something once a week to give their editor for the science columns, or the science pages. They’re always on the lookout for something, and biological weapons is a nice subject — they’d like to write about that, because it grabs people’s attention.”

So I arranged to either meet, or at least talk to all of these guys. And we got all kinds of articles in the press, and mainly reflecting the views that I had that this was unwise for the United States to pioneer this stuff. We should be in the position to go after anybody else who was doing it even in peacetime and get them to stop, which we couldn’t very well do if we were doing it ourselves. In other words, that meant a treaty. You have to have a treaty, which might be violated, but if it’s violated and you know, at least you can go after the violators, and the treaty will likely stop a lot of countries from doing it in the first place.

So what are the treaties? There’s an old treaty, a 1925 Geneva Protocol. The United States was not a party to it, but it does prohibit the first use of bacteriological or other biological weapons. So the problem was to convince the United States to get on board that treaty.

The very first paper I wrote for the President is called the Geneva Protocol of 1925. I never met President Nixon, but I did know Henry Kissinger: He’d been my neighbor at Harvard, the building next door to mine. There was a good lunch room on the third floor. We both ate there. He had started an arms control seminar, met every month. I went to that, all the meetings. We traveled a little bit in Europe together. So I knew him, and I wrote papers for Henry knowing that those would get to Nixon. The first paper that I wrote, as I said, was “The United States and the Geneva Protocol.” It made all these arguments that I’m telling you now about why the United States should not be in this business. Now, the Protocol also prohibits chemical weapons or the first use of chemical weapons.

Now, I should say something about writing papers for Presidents. You don’t want to write a paper that’s saying, “Here’s what you should do.” You have to put yourself in their position. There are all kinds of options on what they should do. So, you have to write a paper from the point of view of a reader who’s got to choose between a lot of options. He doesn’t have a choice to start with. So that’s the kind of paper you need to write. You’ve got to give every option a fair trial. You’ve got to do your best, both to defend every option and to argue against every option. And you’ve got to do it in no more than a very few number of pages. That’s no easy job, but you can do it.

So eventually, as you know, the United States renounced biological weapons in November of 1969. There was an off the record press briefing that Henry Kissinger gave to the journalists about this. And one of them, I think it was the New York Times guy, said, “What about toxin weapons?”

Now, toxins are poisonous things made by living things, like Botulinum toxin made by bacteria or snake venom, and those could be used as weapons in principle. You can read in this briefing, Henry Kissinger says, “What are toxins?” So what this meant, in other words, is that a whole new review, a whole new decision process had to be cranked up to deal with the question, “Well, do we renounce toxin weapons?” And there were two points of view. One was, “They are made by living things, and since we’re renouncing biological warfare, we should renounce toxins.”

The other point of view is, “Yeah, they’re made by living things, but they’re just chemicals, and so they can also be made by chemists in laboratories. So, maybe we should renounce them when they’re made by living things like bacteria or snakes, but reserve the right to make them and use them in warfare if we can synthesize them in chemical laboratories.” So I wrote a paper arguing that we should renounce them completely. Partly because it would be very confusing to argue that the basis for renouncing or not renouncing is who made them, not what they are. But also, I knew that my paper was read by Richard Nixon on a certain day on Key Biscayne in Florida, which was one of the places he’d go for rest and vacation.

Nixon was down there, and I had written a paper called “What Policy for Toxins.” I was at a friend’s house with my wife the night that the President and Henry Kissinger were deciding this issue. Henry called me, and I wasn’t home. They couldn’t find their copy of my paper. Henry called to see if I could read it to them, but he couldn’t find me because I was at a dinner party. Then Henry called Paul Doty, my friend, because he had a copy of the paper. But he looked for his copy and he couldn’t find it either. Then late that night Kissinger called Doty again and said, “We found the paper, and the President has made up his mind. He’s going to renounce toxins no matter how they’re made, and it was because of Matt’s paper.”

I had tried to write a paper that steered clear of political arguments — just scientific ones and military ones. However, there had been an editorial in the Washington Post by one of their editorial writers, Steve Rosenfeld, in which he wrote the line, “How can the President renounce typhoid only to embrace Botulism?”

I thought it was so gripping, I incorporated it under the topic of the authority and credibility of the President of the United States. And what Henry told Paul on the telephone was: that’s what made up the President’s mind. And of course, it would. The President cares about his authority and credibility. He doesn’t care about little things like toxins, but his authority and credibility… And so right there and then, he scratched out the advice that he’d gotten in a position paper, which was to take the option, “Use them but only if made by chemists,” and instead chose the option to renounce them completely. And that’s how that decision got made.

Ariel: That all ended up in the Biological Weapons Convention, though, correct?

Matthew: Well, the idea for that came from the British. They had produced a draft paper to take to the arms control talks with the Russians and other countries in Geneva, suggesting a treaty to prohibit biological weapons in war — not just the way the Geneva Protocol did, but would prohibit even their production and possession, not merely their use. Richard Nixon, in his renunciation by the United States, what he did was threefold. He got the United States out of the biological weapons business and decreed that Fort Detrick and other installations that had been doing that would hence forward be doing only peaceful things, like Detrick was partly converted to a cancer research institute, and all the biological weapons that had been stock piled were to be destroyed, and they were.

The other thing he did was renounce toxins. Another thing he decided to do was to resubmit the Geneva Protocol to the United States Senate for its advice and approval. And the last thing was to support the British initiative, and that was the Biological Weapons Convention. But you could only get it if the Russians agreed. But eventually, after a lot of negotiation, we got the Biological Weapons Convention, which is still in force. A little later we even got the Chemical Weapons Convention, but not right away because in my view, and in the view of a lot of people, we did need chemical weapons. Until we could be pretty sure that the Soviet Union was going to get rid of its chemical weapons, too.

If there are chemical weapons on the battlefield, soldiers have to put on gas masks and protective clothing, and this really slows down the tempo of combat action, so that if you could simply put the other side into that restrictive clothing, you have a major military accomplishment. Chemical weapons in the hands of only one side would give that side the option of slowing down the other side, reducing the mobility on the ground of the other side. So, until we got a treaty that had inspection provisions, which the chemical treaty does, and the biological treaty does not — well, it has a kind of challenge inspection, but no one’s ever done that, and it’s very hard to make it work — but the chemical treaty had inspection provisions that were obligatory, and have been extensive: with the Russians visiting our chemical production facilities, and our guys visiting theirs, and all kinds of verification. So that’s how we got the Chemical Weapons Convention. That was quite a bit later.

Max: So, I’m curious, was there a Matthew Meselson clone on the British side, thanks to whom the British started pushing this?

Matthew: Yes. There were of course, numerous clones. And there were numerous clones on this side of the Atlantic, too. None of these things could ever be ever done by just one person. But my pal Julian Robinson, who was at the University of Sussex in Brighton, he was a real scholar of chemical and biological weapons, knows everything about them, and their whole history, and has written all of the very best papers on this subject. He’s just an unbelievably accurate and knowledgeable historian and scholar. People would go to Julian for advice. He was a Mycroft. He’s still in Sussex.

Ariel: You helped start the Harvard Sussex Program on chemical and biological weapons. Is he the person you helped start that with, or was that separate?

Matthew: We decided to do that together.

Ariel: Okay.

Matthew: It did several things, but one of the main things it did was to publish a quarterly journal, which had a dispatch from Geneva — progress towards getting the Chemical Weapons Convention — because when we started the bulletin, the Chemical Convention had not yet been achieved. There were all kinds of news items in the bulletin; We had guest articles. And it finally ended, I think, only a few years ago. But I think it had a big impact; not only because of what was in it, but because, also, it united people of all countries interested in this subject. They all read the bulletin, and they all got a chance to write in the bulletin as well, and they occasionally meet each other, so it had an effect of bringing together a community of people interested in safely getting rid of chemical weapons and biological weapons.

Max: This Biological Weapons Convention was a great inspiration for subsequent treaties, first the ban on biological weapons, and then various other kinds of weapons, and today, we have a very vibrant debate about whether there should be also be a ban on lethal autonomous weapons, and inhumane uses of A.I. So, I’m curious to what extent you got lots of push-back back in those days from people who said, “Oh this is a stupid idea,” or, “This is never going to work,” and what the lessons are that could be learned from that.

Matthew: I think that with biological weapons, and also, but to a lesser extent, with chemical weapons, the first point was we didn’t need them. We had never really accepted World War I — when we were involved in the use of chemical weapons, that had been started. But it was never something that the military liked. They didn’t want to fight a war by encumberment. Biological weapons for sure not, once we realized that to make cheap weapons, they could get into the hands of people who couldn’t afford nuclear weapons, was idiotic. And even chemical weapons are relatively cheap and have the possibility of covering fairly large areas at a low price, and also getting into the hands of terrorists. Now, terrorism wasn’t much on anybody’s radar until more recently, but once that became a serious issue, that was another argument against both biological and chemical weapons. So those two weapons really didn’t have a lot of boosters.

Max: You make it sound so easy though. Did it never happen that someone came and told you that you were all wrong and that this plan was never going to work?

Matthew: Yeah, but that was restricted to the people who were doing it, and a few really eccentric intellectuals. As evidence of this: in the military, the office which dealt with chemical and biological weapons, the highest rank you could find in that would be a colonel. No general, just a colonel. You don’t get to be a general in the chemical corps. There were a few exceptions, basically old times, as kind of a left over from World War I. If you’re a part of the military that never gets to have a general or even a full colonel, you ain’t got much influence, right?

But if you talk about the artillery or the infantry, my goodness, I mean there are lots of generals — including four star generals, even five star generals — who come out of the artillery and infantry and so on, and then Air Force generals, and fleet admirals in the Navy. So that’s one way you can quickly tell whether something is very important or not.

Anyway, we do have these treaties, but it might be very much more difficult to get treaties on war between robots. I don’t know enough about it to really have an opinion. I haven’t thought about it.

Ariel: I want to follow up with a question I think is similar, because one of the arguments that we hear a lot with lethal autonomous weapons, is this fear that if we ban lethal autonomous weapons, it will negatively impact science and research in artificial intelligence. But you were talking about how some of the biological weapons programs were repurposed to help deal with cancer. And you’re a biologist and chemist, but it doesn’t sound like you personally felt negatively affected by these bans in terms of your research. Is that correct?

Matthew: Well, the only technically really important thing — that would have happened anyway — that’s radar, and that was indeed accelerated by the military requirement to detect aircraft at a distance. But usually it’s the reverse. People who had been doing research in fundamental science naturally volunteered or were conscripted to do war work. Francis Crick was working on magnetic torpedoes, not on DNA or hemoglobin. So, the argument that a war stimulates basic science is completely backwards.

Newton, he was director of the mint. Nothing about the British military as it was at the time helped Newton realize that if you shoot a projectile fast enough, it will stay in orbit; He figured that out by himself. I just don’t believe the argument that war makes science advance. It’s not true. If anything, it slows it down.

Max: I think it’s fascinating to compare the arguments that were made for and against a biological weapons ban back then with the arguments that are made for and against a lethal autonomous weapons ban today, because another common argument I hear for why people want lethal autonomous weapons today is because, “Oh, they’re going to be great. They’re going to be so cheap.” That’s like exactly what you were arguing is a very good argument against, rather than for, a weapons class.

Matthew: There’s some similarities and some differences. Another similarity is that even one autonomous weapon in the hands of a terrorist could do things that are very undesirable — even one. On the other hand, we’re already doing something like it with drones. There’s a kind of continuous path that might lead to this, and I know that the military and DARPA are actually very interested in autonomous weapons, so I’m not so sure that you could stop it, both because it’s continuous; It’s not like a real break.

Biological weapons are really different. Chemical weapons are really different. Whereas autonomous weapons still are working on the ancient primitive analogy of hitting a man with your fist, or shooting a bullet. So long as those autonomous weapons are still using guns, bullets, things like that, and not something that is not native to our biology like poison. But with a striking of a blow you can make a continuous line all the way through stones, and bows and arrows, and bullets, to drones, and maybe autonomous weapons. So discontinuity is different.

Max: That’s an interesting challenge, deciding where exactly one draws the line to be more challenging in this case. Another very interesting analogy, I think, between biological weapons and lethal autonomous weapons is the business of verification. You mentioned earlier that there was a strong verification protocol for the Chemical Weapons Convention, and there have been verification protocols for nuclear arms reduction treaties also. Some people say, “Oh, it’s a stupid idea to ban lethal autonomous weapons because you can’t think of a good verification system.” But couldn’t people have said that also as a critique of the Biological Weapons Convention?

Matthew: That’s a very interesting point, because most people who think that verification can’t work have never been told what’s the basic underlying idea of verification. It’s not that you could find everything. Nobody believes that you could find every missile that might exist in Russia. Nobody ever would believe that. That’s not the point. It’s more subtle. The point is that you must have an ongoing attempt to find things. That’s intelligence. And there must be a heavy penalty if you find even one.

So it’s a step back from finding everything, to saying if you find even one then that’s a violation, and then you can take extreme measures. So a country takes a huge risk that another country’s intelligence organization, or maybe someone on your side who’s willing to squeal, isn’t going to reveal the possession of even one prohibited object. That’s the point. You may have some secret biological production facility, but if we find even one of them, then you are in violation. It isn’t that we have to find every single blasted one of them.

That was especially an argument that came from the nuclear treaties. It was the nuclear people who thought that up. People like Douglas McEachin at the CIA, who realized that there’s a more sophisticated argument. You just have to have a pretty impressive ability to find one thing out of many, if there’s anything out there. This is not perfect, but it’s a lot different from the argument that you have to know where everything is at all times.

Max: So, if I can paraphrase, is it fair to say that you simply want to give the parties to the treaty a very strong incentive not to cheat, because even if they get caught off base one single time, they’re in violation, and moreover, those who don’t have the weapons at that time will also feel that there’s a very, very strong stigma? Today, for example, I find it just fascinating how biology is such a strong brand. If you go ask random students here at MIT what they associate with biology, they will say, “Oh, new cures, new medicines.” They’re not going to say bioweapons. If you ask people when was the last time you read about a bioterrorism attack in the newspaper, they can’t even remember anything typically. Whereas, if you ask them about the new biology breakthroughs for health, they can think of plenty.

So, biology has clearly very much become a science that’s harnessed to make life better for people rather than worse. So there’s a very strong stigma. I think if I or anyone else here at MIT tried to secretly start making bioweapons, we’d have a very hard time even persuading any biology grad student to want to work with them because of the stigma. If one could create a similar stigma against lethal autonomous weapons, the stigma itself would be quite powerful, even absent the ability to do perfect verification. Does that make sense?

Matthew: Yes, it does, perfect sense.

Ariel: Do you think that these stigmas have any effect on the public’s interest or politicians’ interest in science?

Matthew: I think there’s still great fascination of people with science. I think that the exploration of space, for example: lots of people, not just kids — but especially kids — that are fascinated by it. Pretty soon, Elon Musk says in 2022, he’s going to have some people walking around on Mars. He’s just tested that BFR rocket of his that’s going to carry people to Mars. I don’t know if he’ll actually get it done but people are getting fascinated by the exploration of space, are getting fascinated by lots of medical things, are getting desperate about the need for a cure for cancer. I myself think we need to spend a lot more money on preventing — not curing but preventing cancer — and I think we know how to do it.

I think the public still has a big fascination, respect, and excitement from science. The politicians, it’s because, see, they have other interests. It’s not that they’re not interested or don’t like science. It’s because they have big money interests, for example. Coal and oil, these are gigantic. Harvard University has heavily invested in companies that deal with fossil fuels. Our whole world runs on fossil fuels mainly. You can’t fool around with that stuff. So it becomes a problem of which is going to win out, your scientific arguments, which are almost certain to be right, but not absolutely like one and one makes two — but almost — or the whole economy and big financial interests. It’s not easy. It will happen, we’ll convince people, but maybe not in time. That’s the sad part. Once it gets bad enough, it’s going to be bad. You can’t just turn around on a dime and take care of disastrous climate change.

Max: Yeah, this is very much the spirit of course, of the Future Life Institute, that Ariel’s podcast is run by. Technology, what it really does, it empowers us humans to do more, either more good things or more bad things. And technology in and of itself isn’t evil, nor is it morally good; It’s a tool, simply. And the more powerful it becomes, the more crucial it is that we also develop the wisdom to steer the technology for good uses. And I think what you’ve done with your biology colleagues is such an inspiring role model for all of the other sciences, really.

We physicists still feel pretty guilty about giving the world nuclear weapons, but we’ve also gave the world a lot of good stuff, from lasers, to smartphones and computers. Chemists gave the world a lot of great materials, but they also gave us, ultimately, the internal combustion engine and climate change. Biology, I think more than any other field, has clearly ended up very solidly on the good side. Everybody loves biology for what it does, even though it could have gone very differently, right? We could have had a catastrophic arms race, a race to the bottom, with one super power outdoing the other in bioweapons, and eventually these cheap weapons being everywhere, and on the black market, and bioterrorism every day. That future didn’t happen, that’s why we all love biology. And I am very honored to get to be on this call here with you, so I could personally thank you for your role on making it this way. We should not take this for granted, that it’ll be this way with all sciences, the way it’s become for biology. So, thank you.

Matthew: Yeah. That’s all right.

I’d like to end with one thought. We’re learning how to change the human genome. They won’t really get going for a while, and there’s some problems that very few people are thinking about. Not the so-called off target effects, that’s a well-known problem — but there’s another problem that I won’t go into, but it’s called epistasis. Nevertheless, 10 years from now, 100 years from now, 500 years from now, sooner or later we’ll be changing the human genome on a massive scale, making people better in various ways, so-called enhancements.

Now, a question arises. Do we know enough about the genetic basis of what makes us human to be sure that we can keep the good things about being human? What are those? Well, compassion is one. I’d say curiosity is another. Another is the feeling of needing to be needed. That sounds kind of complicated, I guess, but if you don’t feel needed by anybody — there’s some people who can go through life and they don’t need to feel needed. But doctors, nurses, parents, people who really love each other: the feeling of being needed by another human being, I think, is very pleasurable to many people, maybe to most people, and it’s one of the things that’s of essence of what it means to be human.

Now, where does this all take us? It means that if we’re going to start changing the human genome in any big time way, we need to know, first of all, what we most value in being human, and that’s a subject for the humanities, for everybody to talk about, think about. And then it’s a subject for the brain scientists to figure out what’s the basis of it. It’s got to be in the brain. But what is it in the brain? And we’re miles and miles and miles away in brain science from being able to figure out what is it in the brain — or maybe we’re not, I don’t know any brain science, I shouldn’t be shooting off my mouth — but we’ve got to understand those things. What is it in our brains that makes us feel good when we are of use to someone else?

We don’t want to fool around with whatever those genes are — do not monkey with those genes unless you’re absolutely sure that you’re making them maybe better — but anyway, don’t fool around. And figure out in the humanities, don’t stop teaching humanities. Learn from Sophocles, and Euripides, and Aeschylus: What are the big problems about human existence? Don’t make it possible for a kid to go through Harvard — as is possible today — without learning a single thing from Ancient Greece. Nothing. You don’t even have to use the word Greece. You don’t have to use the word Homer or any of that. Nothing, zero. Isn’t that amazing?

Before President Lincoln, everybody, to get to enter Harvard, had to already know Ancient Greek and Latin. Even though these guys were mainly boys of course, and they were going to become clergymen. They also, by the way — there were no electives — everyone had to take fluctions, which is differential calculus. Everyone had to take integral calculus. Every one had to take astronomy, chemistry, physics, as well as moral philosophy, et cetera. Well, there’s nothing like that anymore. We don’t all speak the same language because we’ve all had such different kinds of education, and also the humanities just get a short shrift. I think that’s very short sighted.

MIT is pretty good in humanities, considering it’s a technical school. Harvard used to be tops. Harvard is at risk of maybe losing it. Anyway, end of speech.

Max: Yeah, I want to just agree with what you said, and also rephrase it the way I think about it. What I hear you saying is that it’s not enough to just make our technology more powerful. We also need the humanities, and our humanity, for the wisdom of how we’re going to manage our technology and what we’re trying to use it for, because it does no good to have a really powerful tool if you aren’t wise and use it for the right things.

Matthew: If we’re going to change, we might even split into several species. Almost all of the other species have very close other species: neighbors. Especially if you can get them separated — there’s a colony on Mars and they don’t travel back and forth much — species will diverge. It takes a long, long, long, long time, but the idea there, like the Bible says, that we are fixed, nothing will change, that’s of course wrong. Human evolution is going on as we speak.

Ariel: We’ll end part one of our two-part podcast with Matthew Meselson here. Please join us for the next episode which serves as a reminder that weapons bans don’t just magically work. But rather, there are often science mysteries that need to be solved in order to verify whether a group has used a weapon illegally. In the next episode, Matthew will talk about three such scientific mysteries he helped solve, including the anthrax incident in Russia, the yellow rain affair in Southeast Asia, and the research he did that led immediately to the prohibition of Agent Orange. So please join us for part two of this podcast, which is also available now.

As always, if you’ve been enjoying this podcast, please take a moment to like it, share it, and maybe even leave a positive review. It’s a small action on your part, but it’s tremendously helpful for us.